Today’s post is an anonymous, personal reflection on the experience of sexual exploitation in childhood. The reflection also draws in the biblical story of Amnon’s rape of Tamar (2 Samuel 13). On the one hand this is a declaration reminiscent of #MeToo but it is also an expression of defiant and articulate silence and a reminder that there isn’t a single, let alone a ‘right’ response to sexual violation.

********************

“I come from a place where breath, eyes, and memory are one, a place from which you carry your past like the hair on your head.”

Edwidge Danticant, Breath, Eyes, Memory

I have always been intrigued by silence; it has given me the space to observe and understand people. Because of my mother’s influential position as a prayer warrior within the Christian community, our house was constantly filled with people, especially troubled women. Since I was just a young girl, invisible in a patriarchal world, no one seemed to notice me. So I just listened and studied the women who came with their stories, women who were under-appreciated, disrespected, unloved, silenced, cheated on, battered, and raped. Too many stories to tell. Yet the advice was all too familiar, quietly endure the mistreatment and abuse for the sake of the children, for the family.

It was the same advice that my mother kept for our own family. And so I was silent when I had to deal with my own sexual molestation. When I was young, I didn’t have the emotional capacity and definitely not the words to understand what was happening. My mother knew what was happening but she failed to protect me because it was a family member she wanted to protect even more. It was an ongoing shameful “event” that was confused with love, loyalty, and duty to the family. All integrally connected to Korean cultural values that I only understood to be burdensome in my adulthood. My mother, herself a victim/survivor of molestation and rape, tried to normalize the “event.” It happens in all families and it was my responsibility from making it happen yet again. I, the woman, had the power to say no and avoid the situation. Since it was understood that men had no self-control, he could not be expected or punished to stop. But I was just a child, confused, not a woman. So I was silenced or had no choice but to be silent. I would not have known what to say or to whom I would have spoken. After all, it happens in all families. So I tried to listen to my mother’s advice, to avoid situations and learned to say, “No.” But it was at the cost, the loss of a loving relationship that I needed and valued. Of course, the perpetrator had his reasons, perhaps justifiable to him, for his perversion but that is not my story to tell. The burden is on him to explain his behavior to the world and God. But most likely, he will choose silence for fear of jeopardizing his standing in the family and without question, his community. I just wanted to make sure that it never ever happened again in the family. Never. And it never did.

When I came into my personhood, I chose to be silent about the “event.” Perhaps I was ashamed and somehow blamed myself for not stopping the “event.” But more than anything, I still did not know how to express the inexplicable rage, hatred, self-loathing, and disgust that lied underneath. And as always, I felt the responsibility to protect the perpetrator and my family which had a reputation to keep in the community. I was not equipped emotionally to share this story with my close friends. I remember just uttering a few words to a couple of people who were victims of molestation to make a point. But it was all in passing, nothing to brood over or deal with. This was the norm for a dutiful person who wanted to honor her mother’s implicit wishes.

Even when I was heavily influenced by the Oprah-era of needing to share one’s life publicly, I chose silence. I knew the rhetoric that silence equaled death and courageous women were the ones who came out with their stories. After all, truth or finding one’s voice liberates the person. However, I chose silence to deal with the “event.” I still did not have the words to describe the “inexplicable.” How does one talk about trauma? What words can encapsulate the “event”? Who will be able to understand the mixed emotions of being hurt by a loved one?

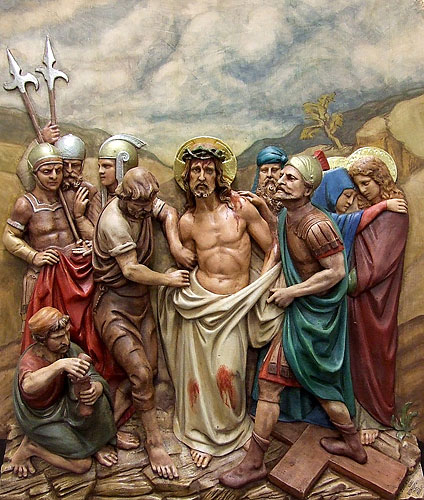

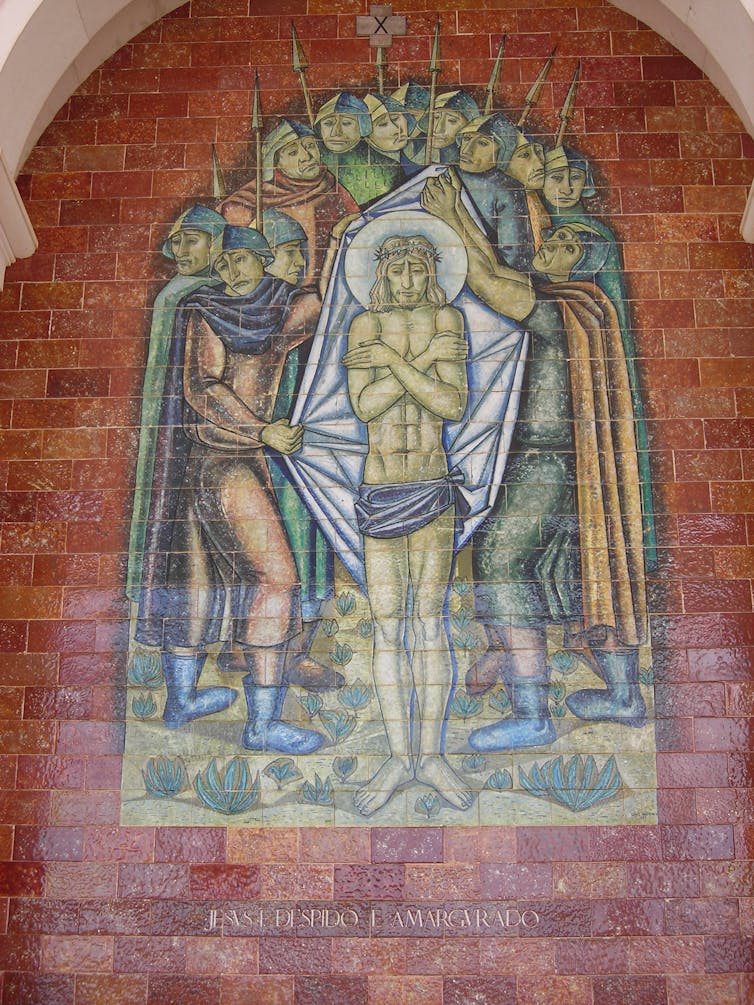

But I have decided now to talk about the “event” through the story of Tamar (2 Sam 13). In the biblical story the daughter of King David, a virgin princess, is raped by her half-brother, Amnon. The author explains that he was “tormented” because he was madly in love with a virgin who happens to be his sister. He could not help himself; he was ill with lust so he had to possess her sexually. And he does, forcibly against the wishes of his vocal sister. She resists, fights, but he overpowers her. Afterwards, she tries to talk sense into her half-brother, begging him to marry her so that they do have to bear the shame. He does not listen; he is after all the crown prince, the heir apparent to the throne of Israel. She will be shamed, not him. Why would he listen to a woman? He commands the servant to kick her out, whereupon she puts ashes on her head, tears her garment, and leaves the premise crying out loud. She rightfully mourns for herself.

Everyone in the palace would have known; it would not have been a mystery that Amnon had raped his sister. Yet everyone was silent. The servants were silent. Amnon disappeared into the background and therefore became silent. Her father, the almighty King David knew but he remained silent. Absalom, her full brother, found out but he too kept silent. And it would appear that Tamar was silenced or became silent. Yet their silences were not the same.

The servants did not have the power to speak; they would have spoken only at the cost of their livelihood or lives. If they spoke of the “event,” it would have been in hushed tones. Amnon himself chooses silence because he probably did not believe he wronged anyone. Why would he talk about a trifling matter? Is he not the prince who will one day rule the kingdom as he saw fit? King David, the father and executor of justice, should and could have punished his son and uplifted his daughter but he chooses silence. He did not want to punish his beloved son. But then what about his daughter?! He, by his silence, became complicit in Amnon’s crime. Absalom, the rightful defender of his sister’s honor, also decides to remain silent. His silence hid his determination to kill Amnon. But who knows if he was defending his sister or making a run for the throne. All three men in position of authority should have spoken up for Tamar; yet they chose silence to protect, to ensure their own power.

Then what about Tamar’s silence? Scholars have argued that Tamar was silenced; Absalom asked her to remain quiet. I argue just the opposite. She chooses to remain silent. Given her characterization throughout the story in which she, a woman, speaks against her brother is quite significant. No female biblical character is more vocal than Tamar. A woman who demonstrably cries out her pain most likely could not be silenced by her brother, Absalom. Yet her silence is not quiet but defiant. Rather than use words, she decides to speak through her “desolated” body. It is not clear if the court historian had personally experienced or knew of her story but s/he aptly encapsulates Tamar’s response with the word, “desolated” (2 Sam 13:20).

The Hebrew word conjures imagery of devastation in the aftermath of war, the absence of life in the midst of charred ruins.

She embodied the “event” so that every sigh, every pained look, every deadly silence bespoke the devastation of the violent rape. She did not need to utter a word because she had become a living monument to the “event.” So she speaks without words; she breathes her pain. And everyone would have experienced and known of the “event” through her very presence. Though men have refused to publicly acknowledge the “event,” she used her desolated body to tell her story. She created a space that defied the men of power, ultimately undermining their authority. This is real power, power to throttle or overthrow unjust leaders.

The emboldening story of Tamar’s rape and her desolation has given meaning to my silence. I do not necessarily think a survivor’s silence is an act of acquiescence to the cultural silencing of women.[1] Yes, one could argue that my mother had been silenced by the expectations of her culture. It was shameful for a woman to discuss sex, especially sexual violence that was committed against her body by a family member, a much older half-brother. However, she embodied the desolation in the silence. She, who constantly remembered and repeatedly told stories of her emotional, verbal, and physical abuse, did not utter a word about the sexual abuse. But I knew she had been molested before she even mentioned it. Her body language bore the desolation. She only said a few words to me just once, not twice. And I knew of the rape because I was physically there. I was not a direct witness but I knew with all the yelling, bashing of fists one particular night that a rape followed. I just knew. I did not know the word for the violent violation but I knew it was the “unspeakable” act of terror. She did not say anything. She again bore the shame of the event and I have inherited her pain. I bear in my body the burden of her rape. But again I have chosen to be silent about her story.

I can hear voices in my head the words of my Western education – “you have been silenced by your family, by your traditions, by your oppressive culture.” Perhaps. But like Tamar, I know that my silence has been an act of defiance. First, it has given me the space to formulate my own narrative of the trauma. I own the story and in my silence, I have refused to acquiesce to the counter-stories created by my mother and perpetrator. Second, silence has allowed me to mourn the pain on my own terms. No one has been able to dictate on how and why I should feel the way I do. Third, I have been able to share my story through my desolated body, not through words but my very presence. I have found that words almost always fail but silence embraces all – the tempest of emotions, the pain, the profound sadness, the confusion. In other words, silence allowed me to be all and nothing at all.[2] And it is through this choice that I have forced the perpetrator to break, to apologize. Interestingly, that was not I wanted. I had forgiven him a long time ago. Nothing would have given back my innocence, my trust, my childhood. No. All I really wanted was him to acknowledge his perversion, to admit his culpability and therefore find a road to his own healing. As for my mother, she is too broken to understand her role in my trauma. She utters a few words because she sees my pain in my silence. But I do not want to hurt her more as Buki, a character who had undergone female circumcision in Breath, Eyes, Memory writes to her dead grandmother:

Because of you, I feel like a helpless cripple. I sometimes want to kill myself. All because of what you did to me, a child who could not say no, a child who could not defend herself. It would be easy to hate you, but I can’t because you are part of me. You are me.[3]

It is in the silence that I have been able to express all the raging emotions and it is through my desolation that I have been able to tell my story, my version of the “event.”

Therefore, I do not believe in asking, encouraging, and definitely not forcing women to verbally share their stories. If we just listen to their defiant silence and observe their desolated bodies, we will be able to piece their stories. For me, it is the silence of the perpetrators and their complicit partners who should be encouraged, perhaps forced to speak about their acts of violence against women. They should be shamed for their cowardice in wanting to hide behind a deafening wall of silence. They should be forced to acknowledge and speak about their crimes.

You may ask. Why have I broken my silence now? I felt a responsibility to a community of women who have chosen to remain defiantly silent. I laud their decision to silently speak of the atrocities committed against them. They may not use words but in their very being, in their embodied desolation, they have and continue to share their stories. And their stories resonate with the stories told by other women. Think about it. Despite all the silence around Tamar, her story is included in the Court History in the Bible. And so her story of her desolated body echoes to this day. She has spoken so loudly through her silence that now everyone knows her story. So we all should listen to her cries and say, no more. Never again, Tamar.

Dedicated to a woman whose desolating silence has inspired me to write this story.

[1] I am not including numerous instances in which women are forcibly silenced. I am speaking of instances in which women have the choice, the privilege to choose between speech and silence.

[2] After much contemplation over silence, I have a deeper appreciation of the divine name, Yahweh (“I am/I will be”). It allows God to be present without being defined, without being named.

[3] Edwidge Danticat, Breath, Eyes, Memory (New York: Soho, 2015), 206.