The Shiloh Project is excited to announce the launch of our latest creative endeavour: the Bloody Bible podcast. Hosted by Shiloh co-directors Em Colgan and Caz Blyth, the podcast takes a deep dive into some of the violent and bloody traditions that are found throughout the Bible, including stories of murder, genocide, colonialism, rape, intimate partner violence, coercive control, and sex trafficking. Em and Caz explore these violent tales, drawing connections to contemporary cases of crime and criminality. What they discover along the way is that the violence we read about in ancient biblical texts remains all too familiar today.

The inspiration for this podcast grew from Caz and Em’s mutual fascination with all things related to true crime. During their many conversations about the topic, they started to recognise that true crime stories share many patterns and themes with biblical narratives of violence, including the perilous potential of human emotions such as envy, anger, and shame; the violent foundations of patriarchal power and toxic masculinity; the sexualization of “dangerous” women; the timelessness of rape culture ideologies; and the erasure of certain victims by virtue of their race, class, sexuality, or gender. The Bloody Bible podcast explores these themes in depth and considers how narratives of crime and criminality – both ancient and contemporary – can shine a light on the socio-cultural, emotional, and ideological forces that underpin so much violence in our families and communities

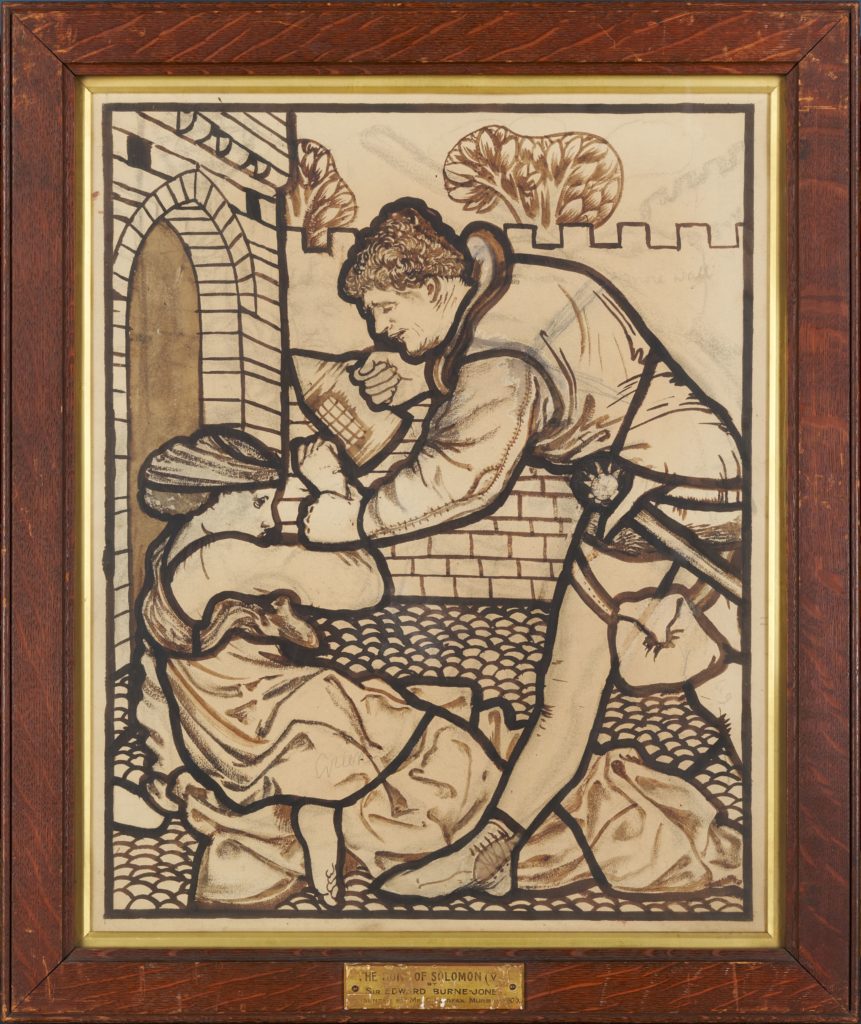

To get a taster of some of the texts and topics covered in the Bloody Bible, listen to the podcast trailer here. The first episode will be available on 1 June 2022, where Caz and Em take a close look at the Bible’s first murder mystery – the killing of Abel by his brother Cain (Genesis 4). Subsequent episodes will be available weekly throughout this 11-part series.

The podcast is co-produced, recorded, and edited by Richard Bonifant, and is supported by funding from the United Kingdom Arts and Humanities Research Council as part of the Shiloh Project research grant. It will be available on Apple Podcasts and Spotify, and you can also find each episode on the podcast website.

You can follow the Bloody Bible on Twitter (@BloodyBiblePod), Instagram (@BloodyBiblePodcast), and Facebook (@TheBloodyBiblePodcast).