Today is International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, designated as Orange Day by the UN Women campaign Say No, UNiTE launched in 2009 to mobilize civil society, activists, governments and the UN system in order amplify the impact of the UN Secretary-General’s campaign, UNiTE to End Violence against Women. Participants the world over are encouraged to wear a touch of orange in solidarity with the cause – the colour symbolizes a brighter future and a world free from violence against women and girls.

The 2018 theme is Orange the World: #HearMeToo and like previous editions, today marks the launch of 16 days of activism that will conclude on 10 December 2018, International Human Rights Day.

To mark International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, and to kick off our daily interviews with activists during the 16 Days of Activism period, we speak to Professor Musa Dube (University of Botswana) about her academic activism and her hopes for the future.

———————————————————

Tell us about yourself! Who are you and what do you do?

My name is Musa W. Dube from Botswana. I work for the University of Botswana as a scholar of the New Testament. My research interest is primarily in reading the New Testament for liberation, which often involves reading for gender, postcolonial, cultural, Earth and international justice. I often interrogate texts for various forms of oppression as well as make attempts to re-read for liberation.

For the past twenty-one years, I have been active working with religious communities in the struggle against HIV and AIDS. This epidemic, which has claimed millions of lives in three decades, is an epidemic within other epidemics that is driven and propelled by social inequalities. These inequalities include economic, gender, racial and age dimensions, as well as inequalities of sexual orientation and identity. With HIV and AIDS we learnt that the biggest violence we unleash on any group of people, and on the whole Creation Community, begins with structural sins that silence and marginalize creation members from their dignity and liberation to live whole lives. Violence is therefore founded upon the structural sins of patriarchy, imperialism, racism, heteronormativity, anthropocentricism etc., which propound worldviews that legitimize the marginalization of the Other. Gender-based violence, sexism and rape are merely symptoms of the foundational structural sin, which is patriarchy.

HIV and AIDS activism has stood up to patriarchy and has called for the re-imagination of masculinities. And so, three years ago, I got involved in a movement that culminated in the formation of Pitso ya Banna, an association that seeks to provide space for men to discuss what it means to be a man, as well as to interrogate troubling masculinities and to provide models for liberating masculinities, that do not embrace violence, or depend on subjugation of women.

How do you think the Shiloh Project’s work on religion and rape culture can add to and enrich discussion and action on the topic of gender activism today? Is there more we can do? What else should we post?

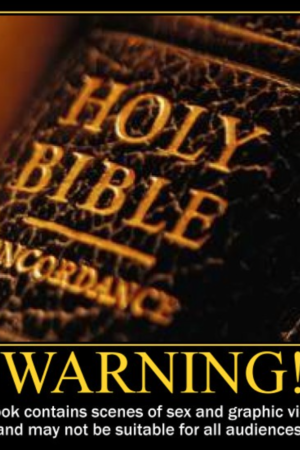

Since religion remains a space that gathers communities under some agreed high ethical reflections, a project that looks into religion and rape is definitely important and stands a great chance towards building communities of gender justice. Most religious traditions and communities need conversations, regarding their scriptures, beliefs and practices concerning gender-based violence, and rape in particular. They need skills of naming and recognizing sexual violence and naming it as unacceptable sin.

It is commonly assumed that members of religious communities are not sexually violent, but research indicates otherwise. It is also common that holy texts that deal with rape and gender-based violence more generally do not get read in worship, or if they are read, they often get interpreted from perspectives that normalize violence against women. Empowering faith communities to break the silence concerning rape and to equip them with skills of reading such texts to expose ideological structures that embrace sexual violence and gender inequalities is vital. Further, religious communities, at least here in Botswana, need to be empowered with skills of counselling survivors of rape.

Recent rape scandals in a Pentecostal church in South Africa, where young teenagers were subjugated to rape by their pastor, seemingly with the knowledge of the congregation, indicate that both religious leaders and their congregants need to be trained to confront and resist rape. This must include training to empower them to blow the whistle when violence happens.

In the year ahead, how will you contribute to advancing the aims and goals of The Shiloh Project?

Theology and Religious Studies members of the University of Botswana are active members of the Shiloh Project. Indeed, the Project is partly hosted in my home department. I am committed to and skilled in reading and re-reading texts for exposing all forms of oppressions. Moreover, I can offer positive models of justice and gender justice in particular. Last year I read the story of the rape of Dinah (Genesis 34), exploring how it intersects with colonial desires and ethnic difference. Therefore, I am already strategically placed to interact and collaborate with the Shiloh Project in multiple ways that can advance its aims and goals.

I am also hoping that through Pitso ya Banna, we will collaborate in reaching faith communities and expanding the spaces where discussions concerning non-violent masculinities can be opened. Collaborating with the Shiloh Project might allow us to break the silence concerning rape in faith communities and to empower religious communities to speak out against rape and other forms of violence, within their congregations and in the general public.

In general, my assumption concerning violence is that it begins with structural sin, which is then manifested in various forms, including acts such as rape. The core of addressing gender-based violence, and rape in particular, should therefore begin by empowering religious communities to name patriarchy as a foundational sin, which is inconsistent with any form of acknowledging the Divine Creator.