Professor David Tombs has written an article, ‘Should the stripping of Jesus be labelled sexual abuse?’ for Otago Daily Times. You can read it here.

Find out more about the work of Professor Tombs at his project website.

Professor David Tombs has written an article, ‘Should the stripping of Jesus be labelled sexual abuse?’ for Otago Daily Times. You can read it here.

Find out more about the work of Professor Tombs at his project website.

Katie Edwards, University of Sheffield and M J C Warren, University of Sheffield

It is the start of Lent, a time when Christians reflect on the upcoming Passion of Jesus. Jesus is held up as an example of steadfastness in the face of oppression by malevolent forces. He shows strength through his silence, approaching his suffering willingly.

Throughout the ongoing #MeToo movement Jesus has been invoked by Christian communities as a co-sufferer and promoted as a model for redemptive suffering, particularly in the face of abuse. But is Jesus’s silence a troubling model for victims of sexual assault?

One of the hallmarks of Jesus’s portrayal in popular culture is his silence in the face of Pontius Pilate’s interrogation. This image of silence comes from the three Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke’s versions of Jesus’s trial.

When Jesus does speak, his words are brief, cryptic, and taken from the Gospel of John rather than the other three, where Jesus’s silence is emphasised.

In Matthew and in Mark, the entire trial scene takes place in four verses; in Luke, where there is slightly more input from “the multitudes” as well as a second trial in front of Herod, we are done in eight verses. Even so, in these gospels, Jesus makes no answer to the charges laid against him.

It’s likely that Matthew, Mark and Luke’s versions depict Jesus’s silence as a way of characterising him as the “Suffering Servant” of Isaiah 53:7. In each case, whether in these gospels or in Isaiah, the image portrayed is one of virtue in silence, and of a pious sacrifice in the face of an unjust world. It is that silence that ultimately kills him.

This contrasts with John’s depiction of the same scene, which takes place over ten verses, more than double the amount of text devoted to the trial in Mark and Matthew’s versions. In John, Jesus is clear about who he is and makes a direct response to accusations; he also corrects Pilate’s misunderstanding about his true identity. This is part of Jesus’ plan – he is clear about his death being the will of God his Father.

But whether he is silent as in Mark or whether he speaks in his own defence as in John, Jesus is sentenced to death and crucified. The end result – suffering, pain, and death – is the same.

Parallels have been drawn between Jesus’s response to his abuse during the Passion and the #MeToo movement. Not least because, like Jesus, the victims of Harvey Weinstein’s alleged abuse have been condemned whether they’ve spoken out or remained silent.

While the torture and crucifixion of Jesus in the Bible is widely accepted, the idea that his abuse included sexual assault is a less established aspect of the Passion narrative.

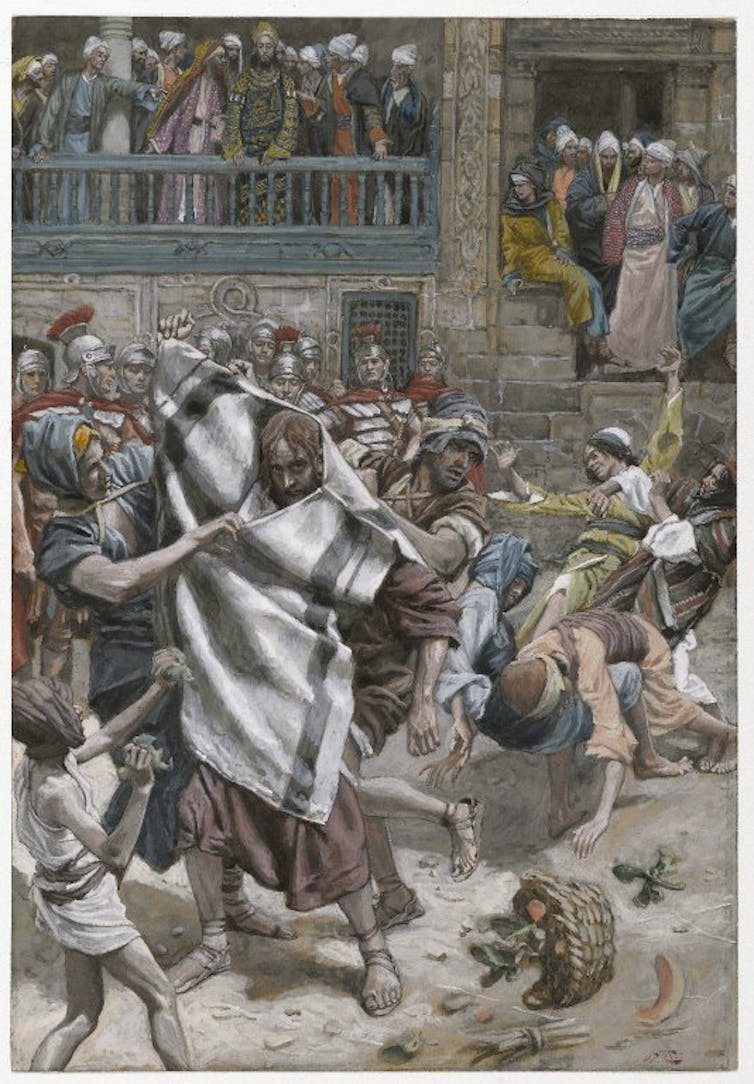

The work of David Tombs at the University of Otago shows that Jesus’s torture included a sexual element. According to the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus is stripped three times and his nakedness is part of his humiliation. Similarly, biblical scholar Wil Gafney has suggested that the crucifixion of Jesus is a form of sexual assault:

I consider … the full range of torture and humiliation to which Jesus of Nazareth was subjected, physical and sexual. The latter is so traumatising for the Church that we have covered it up – literally – covering Jesus’ genitals on our crucifixes … The mocking, taunting, forced stripping of Jesus was a sexual assault. He was, as so many of us are – women and men, children and adult – vulnerable to those who used physical force against him in whatever way they chose.

Throughout the ages, Jesus has been presented as a model of suffering. For instance, in the 18th century, St Paul of the Cross declared that:

The more deeply the cross penetrates, the better; the more deprived of consolation that your suffering is, the purer it will be; the more creatures oppose us, the more closely shall we be united to God.

Silence in the face of abuse, sexual assault and violence, then, becomes glorified and dignified. Some Christian communities have recognised the problems in constructing silence in the face of abuse as virtuous and have taken steps to challenge it.

For example, the hashtags #SilenceisNotSpiritual and #ChurchToo have been developed to offer a counter-narrative to the idea that silent suffering is an emulation of Jesus.

But the backlash to these hashtags, which promote the voices of those who’ve experienced sexual abuse and violence, has included some more troubling connections between Jesus and the #MeToo movement. Some social media commentators have presented Jesus as the perpetrator of sexual assault rather than as the victim.

By using sexual assault as a metaphor for Christ taking Christians by force, penetrating their sin with his righteousness, this view presents Jesus as a perpetrator of sexual assault, undermining the experience of survivors and victims of sexual violence and suggesting that sexual assault might be a potentially positive (or even necessary) experience.

The reaction to Jesus’s silence as well as his self-advocacy presents a troubling model for those who view Jesus as an exemplary victim of abuse, since both silence and speaking out lead to further pain and violence.

![]() This should lead to an interrogation of how we as a society value suffering and especially silent suffering in the wake of #MeToo, but also challenges the notion that victims are obligated to speak out in order to be vindicated. In the end, the blame should still fall firmly on the abusers.

This should lead to an interrogation of how we as a society value suffering and especially silent suffering in the wake of #MeToo, but also challenges the notion that victims are obligated to speak out in order to be vindicated. In the end, the blame should still fall firmly on the abusers.

Katie Edwards, Director SIIBS, University of Sheffield and M J C Warren, Lecturer in Biblical and Religious Studies, University of Sheffield

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

It’s Sexual Abuse and Sexual Violence Awareness Week! This will be followed from 14. February by the One Billion Rising Campaign. Between 14 February and International Women’s Day, on 8 March: look out for regular Shiloh Project updates!

Today, during Sexual Abuse and Sexual Violence Awareness Week is a good time for The Shiloh Project to launch the first post of an occasional series profiling NGOs working actively against rape culture in its myriad forms.

Organizations such as Women’s Shelter and Rape Crisis are very well known and do fantastic and important work. The NGOs we’ll be profiling here are less well known and also important to support, promote and celebrate. First up today is The Cambridge Centre for Applied Research in Human Trafficking, introduced by its Development Director, Rev. Carrie Pemberton Ford …

Tell us about your NGO and your own role.

My name is Carrie Pemberton Ford. I am an Anglican priest and academic, as well as Development Director of the Cambridge Centre for Applied Research in Human Trafficking (CCARHT). The Centre is based in Cambridge (UK). CCARHT is a nonprofit (or not-for-profit) Community Interest Company (CIC), which has Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) recognition from the United Nations office working on counter trafficking.

CCARHT’s vision is to foster applied research that addresses the contemporary global scourge of Human Trafficking, as well as to set this scourge in the wider context of social justice, gender equity, international economic and political power distribution, safer migration and asylum corridors, voice and victim empowerment, and multi-partner co-operation. Human trafficking, as defined by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is the ‘hydra-headed monster’ manifesting in multiple forms that we seek to defeat. This is in line with the Palermo Protocols: three protocols adopted by the United Nations to supplement the 2000 Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. Two of these protocols address human trafficking: one is aimed at suppressing and punishing the trafficking of persons, especially women and children; the second addresses the smuggling of migrants by land, sea and air.

The Shiloh Project explores the intersections between, on the one hand, rape culture, and, on the other, religion. On some of our subsidiary projects we work together with third-sector organizations (including NGOs and FBOs). We also want to raise awareness about and address and resist rape culture manifestations and gender-based violence directly. We’re interested to hear your answers to the following:

How did you get involved in the work you are doing? Do you see religion having impact on the setting where you are working – and how do you perceive that impact?

I was involved in developing victim care responses to human trafficking before the Palermo Protocols became ratified by the UK Government (in 2003). I was the founder of the UK Charity Churches Alert to Sex Trafficking across Europe (CHASTE), and the instigator of the NOT FOR SALE campaign, which raises the issue of the commodification of female lives, along with a minority culture of male lives, within the sex industry. This was my entry into the last fifteen years of working in resistance to human trafficking – in its widest interpretation, which involves labour trafficking (or, slavery), child exploitation, organ trafficking, gamete trafficking and surrogacy, alongside trafficking for sexual exploitation and child abuse within the pornography ‘industry’.

The role of religion is extremely compromised and complex in the challenge of human trafficking. On the one hand, those of us whose faith discourse developed within a culture that values human liberation, gender equality and human rights, recognize religious communities as having powerful potential to interrupt and begin to dismantle cultures of commodification, devaluation of the ‘divine image’ imprint of humanity, and gender-based and racial hierarchies, alongside also age-related abuse, which runs as a major vein across human trafficking and modern slavery. On the other hand, many of these discourses have had long and embarrassing support from patriarchal and systematized ‘canonical’ teachings and their organizational realization.

Consequently, the role of religion is profoundly ambiguous, but offers some dynamic opportunities to address the diverse challenges around human trafficking – from the articulations of state interests, as well as some global conversations around international distribution of resources, value chains, and ensuring safe corridors for the movement of people – all of which address international trafficking – whilst also exploring community accountability, social justice and rape cultures within the domestic and national space.

Whether positive or negative, the role and impact of religion cannot and should not be ignored – including in terms of understanding the full picture of human trafficking.

How do you understand ‘rape culture’ and do you think it can be resisted or detoxified?

Rape culture is about the failure of interpersonal respect and the dereliction of an understanding of gendered difference founded on radical human equality. Rape culture underpins or is underpinned by political and economic hierarchies where the active consent of the other becomes void. Though its etymological background lies in the 1970s feminist movement, with a specific focus on ‘outing’ the ways in which society blames victims of sexual assault and normalizes male sexual violence, rape culture exists up until today and is fed by every societal message where one gender, ethnicity, class, ability, or sexuality becomes dominant and ‘entitled’ to transgress the embodied boundaries of the other.

Rape culture is resisted and detoxified through the raising up of equality, equity, and personal autonomy as rights protected by the State for all its citizens, by the enactment of the United Nations’ inalienable rights (as defined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948), and wherever religious discourse privileges this way of viewing humanity over and against the hierarchical forms which have so often dominated western and other cultures.

Sex trafficking is one form of human trafficking and directly indicative of rape culture. It violates fundamental human rights and human dignity and generates illicit finance for the pimps and traffickers complicit in each and every delivery of a female, male or transgender person into the regional, national or international ‘sex market’. It feeds off the normalization of rape culture whereby the ‘consumer’ does not perceive their transaction as anything other than a ‘purchase’, consent having allegedly been delivered by the agreement to ‘exchange’ a body or bodily service for money.

The relationship between sex trafficking and prostitution more generally is important to disentangle. Important here is the recent and incisive work of Julie Bindel. Her book The Pimping of Prostitution offers some clear insights into the multiple tiers implicit in the notion of ‘consent’ within the context of the global sex industry. She also highlights how the dominant culture refuses to explore the profound power asymmetries present in the embodied politics of this ‘market’ exchange, where the golden mean of the market is rigged by profound systemic inequalities in terms of gender, ethnicity and class.

These matters inform some of the challenges religious discourse needs to address going forward. CCARHT has already developed a theological wing to our work to explore such challenges.

How could those who are interested find out more about your NGO? How can people contribute and where will their money go?

For information and resources, please see the CCARHT website.

We host an annual symposium, which this year is held at Cambridge University from 2nd – 6th July 2018. Our focus will be ‘Terror, Trauma and Transport’. We are hoping to spend the final day of the conference on the theological explorations underpinning the Shiloh Project. (It would be wonderful to attend your conference on 6th July – but that might be difficult, logistically!)

We are also co-curating a summer school on ‘Migrants, Human Rights and Democracy’, to be held in Palermo (Sicily) from June 11th –15th June 2018.

Another upcoming event is a mini conference to be held in London on 13th April. The focus of this is very relevant to the Shiloh Project: namely, the multi-faceted issues and dimensions surrounding the safeguarding and protection of spouses and children in the context of domestic abuse, with particular focus on the roles played by coercive control or institutional inertia of clergy and religious institutions. (Please see: #Hometruths and #Badfaithed or contact me: Carrie@Badfaithed.org)

CCARHT is a not-for-profit organization, and all donations go towards financing publications, mini symposia, research and at-risk-community interventions. These currently involve work in all of Sicily, Catalonia, Macedonia, Ukraine, and the UK.

All our work is focused on developing effective and more sustainable counter-human-trafficking interventions. In the course of this, we look, for example, at international and inter-regional economic fractures, the nexus with migration, creating asylum delivery, victim protection and survivor care, entrepreneurial empowerment for survivors, averting risky behaviours and situations for communities working with unaccompanied minors, supply chain transparency and value chain transformation.

We rely on fee-paying participation of our training symposia, on commissioned reports and donations for the business intervention and training work we are currently undertaking in Sicily, and on co-sponsored arts interventions – the most recent being #Justsex. We are currently seeking £8,000 to develop #Justsex materials to support the ‘Physical Theatre’ work which is currently beginning to find access into School PSHE (Personal and Social Health Education) programmes. (Please contact me directly for more details!)

Please see our library page on www.ccarht.org for our latest reports including our recent submission on ‘Behind Closed Doors: Addressing Human Trafficking, Servitude and Domestic Abuse Through the Black African Churches in London’, which has resulted in the development of a new charity from the cluster working on precisely these issues – namely, ‘Seraphs Tackling Social Injustice’.

What kinds of posts would you like to see on The Shiloh Project blog and what kinds of resources that come into our orbit would be of value to you?

Anything around the way in which rape culture, or patriarchal thinking, or pre-emptive demolition of consent, or gang formation and criminality, works internationally, and cross-culturally, as well as how rape culture is implicitly supported through some religious structures and discourses – and also how rape culture can start to be dismantled through a liberation theology or through a breach in rape culture-supportive theological praxis.

Religion and Rape Culture Conference

We are delighted to announce a one day interdisciplinary conference exploring and showcasing research into the phenomenon of rape culture, both throughout history and within contemporary societies across the globe. In particular, we aim to investigate the complex and at times contentious relationships that exist between rape culture and religion, considering the various ways religion can both participate in and contest rape culture discourses and practices.

We are also interested in the multiple social identities that invariably intersect with rape culture, including gender, disabilities, sexuality, race and class. The Shiloh Project specialises in the field of Biblical Studies, but we also strongly encourage proposals relating to rape culture alongside other religious traditions, and issues relating to rape culture more broadly.

This conference is open to researchers at any level of study, and from any discipline. We invite submissions of abstracts no more than 300 words long and a short bio no later than 19th March. Please indicate whether your submission is for a poster or a presentation. We particularly welcome abstracts on the following topics:

For more information, or to submit an abstract, email shiloh@sheffield.ac.uk

Now available! The recording of Professor David Tombs and Dr Jayme Reaves speaking at the Sheffield Institute for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies (SIIBS) on 16th January 2018.

Click here for more information on the ‘When Did We See You Naked’ Project.

Our White Rose Collaboration Fund project will begin soon and the webpage is already live!

Revelations of pervasive sexual harassment and abuse are emerging from numerous settings. Moreover, educational research shows that such is prevalent already among school pupils. Children as young as 7 experience sexualized name-calling, unwanted touching and appearance-related bullying. Teachers report witnessing such practices and feeling ill-equipped to respond (Women’s and Equalities Committee Report, 2016).

Our multi-disciplinary collaboration brings together academics from Education, English, Biblical and Religious Studies to explore sexism and sexual harassment in secondary school settings using one discrete focus and lens: the role of religious imagery in popular culture (particularly advertising and music videos).

Religious imagery (e.g. the veil, the Cross) is widely used in popular culture both to represent and reinforce ideologies about such complex concepts as ‘sexuality’, ‘purity’, ‘virginity’, or ‘im/morality’. This imagery also conveys notions that casualize or glamourize sexual harassment or violence, reinforce the normativity of heterosexuality, and perpetuate racist associations between Blackness and certain sexual characteristics/desires. Such representations can be regarded as problematic in relation to young people’s understandings of gender, sex and sexualities.

In consultation with secondary schools from all three White Rose regions and a third-sector organization offering gender equality training for school-age girls (Fearless Futures), the network will conduct three pilot workshops with secondary school students (girls and boys) to investigate interactions with religious imagery in popular culture and the ways in which these representations shape understandings of gender, sex and sexualities.

Professor Vanita Sundaram (University of York) will lead the project with Dr Johanna Stiebert (University of Leeds) and Dr Katie Edwards (University of Sheffield), working alongside colleagues Dr Valerie Hobbs (University of Sheffield), Dr Sarah Olive (University of York), Dr Jasjit Singh (University of Leeds), Dr Caroline Starkey (University of Leeds), Ms Sofia Rehman (University of Leeds) and Dr Meredith Warren (University of Sheffield).

Book your place here.

In January 2018 Professor David Tombs will visit SIIBS and deliver a special Shiloh Project lecture on ‘#MeToo Jesus’ with Dr Jayme Reaves.

Professor Tombs is the Howard Paterson Chair of Theology and Public Issues, at the University of Otago, Aotearoa New Zealand. He has a longstanding interest in contextual and liberation theologies and is author of Latin American Liberation Theologies (Brill, 2002). His current research focusses on religion violence and peace and especially on Christian responses to gender-based violence, sexual abuse and torture.

He is originally from the United Kingdom and previously worked at the University of Roehampton in London (1992-2001), and then in Belfast, Northern Ireland, for the Irish School of Ecumenics, Trinity College Dublin (2001-2014) on a conflict resolution and reconciliation programme. He has degrees in theology from Oxford (BA/MA, 1987), Union Theological Seminary New York (STM, 1988), and London (PhD 2004), and in philosophy (MA London, 1993).

Dr Jayme R. Reaves is a public theologian with 20 years experience working on the intersections between theology, peace, conflict, gender, and culture in the US, Former Yugoslavia, Northern Ireland, and Great Britain. Her book, Safeguarding the Stranger: An Abrahamic Theology and Ethic of Protective Hospitality is available from Wipf & Stock or any book retailer. You can find out more at www.jaymereaves.com.

Jayme’s social media links are:

Twitter: @jaymereaves

Facebook: www.facebook.com/JaymeRReaves

——————————————-

#MeToo Jesus: Why Naming Jesus as a Victim of Sexual Abuse Matters

2pm, 16 January, G.03 Jessop West, University of Sheffield

Jayme Reaves and David Tombs

The #MeToo hashtag and campaign created by Tarana Burke in 2007 and popularized by Alyssa Milano in October 2017 has confirmed what feminists have long argued on the prevalence of sexual assault, sexual harassment and sexually abusive behaviour. It has also prompted a more public debate on dynamics of victim blaming and victim shaming which contribute to the silences which typically benefit perpetrators and add a further burden to survivors. As such, the #MeToo movement raises important questions for Christian faith and theology. A church in New York offered a creative response in a sign which adapted Jesus’ words ‘You did this to me’ in Mt 25:40 to read ‘You did this to #MeToo’. This presentation will explore the biblical and theological reasons for naming Jesus as a victim of sexual abuse drawing on earlier work presenting crucifixion as a form of state terror and sexual abuse (Tombs 1999). It will then discuss some of the obstacles to this recognition and suggest why the acknowledgement nonetheless matters. It will argue that recognition of Jesus as victim of sexual abuse can help strengthen church responses to sexual abuses and challenge tendencies within the churches, as well as in wider society, to collude with victim blaming or shaming.

For further reading, see David Tombs, ‘Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse’ in Union Seminary Quarterly Review (1999).

The Shiloh project directors, Caroline Blyth (University of Auckland), Katie Edwards (University of Sheffield) and Johanna Stiebert (University of Leeds), are co-investigators of a successful Worldwide Universities Network research development grant with the University of Ghana.

Katie Edwards and Johanna Stiebert will visit the University of Ghana in 2018. Stay tuned for more updates on the project!

On Day 15, the penultimate day of the 16 Days of Activism, we talk to Dawn Llewellyn, Senior Lecturer in Christian Studies at the University of Chester.

Tell us about yourself…who are you and what do you do?

I’m Dawn and I am Senior Lecturer in Christian Studies, in the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of Chester – I’ve been here for 7 years since finishing my PhD in Religious Studies at Lancaster in 2010. I teach and supervise in the areas of gender and religion, sociology of religion, gender studies, and qualitative methodologies and methods. My work is grounded in feminist qualitative approaches to the study of gender and Christianity: I’ve researched women’s religious reading practices and cultures in relation to literature and the Bible; I’ve also written on feminist generations, third wave feminism, the wave metaphor, and the disciplinary disconnections between feminist/women’s/gender studies and religion.

I’m currently examining women’s reproductive agency in Christianity. In particular, my research focuses on women’s narratives of choice toward motherhood or elective childlessness, and how women mediate and experience the pronatalism circulating through doctrine, scriptures, teachings and the everyday social practices of church life (no surprise, there’s *quite* a lot of pronatalism for women to mediate).

What’s your involvement with The Shiloh Project?

I was delighted and honoured to be asked to become a member when the Shiloh project began. It’s such an important conversation that Katie, Johanna, and Caroline and the team have brought to the fore because religious discourses do inscribe and re-inscribe the inequalities underlying gendered violence and rape culture.

At the moment, I’m very good at tweeting and retweeting about the Shiloh Project and SIIBS, and I have promised to write a piece for the blog! I’m really excited to be part of the work the Project is doing and will do.

How does The Shiloh Project relate to your work?

As a feminist researcher in religious studies, I try in my teaching and research to analyse the ways religion, particularly Christianity, generates gendered injustice, and in particular, how women mediate and negotiate patriarchal and androcentric religious structures. In my previous project, I interviewed Christian and ‘post’ Christian women about the literatures that inspired and resourced their faith and spiritual identities. In the interviews, the women also discussed their biblical reading practices and disclosed their anger at the passages they understood to valorize violence against women. For some participants, this meant they left Christianity or at least turned to women’s writing as a substitute for the Bible – unable to read texts or belong to a tradition that sacralizes narratives that demean women. For others, they resist and reject the text they found problematic. Interrogating how women engage with the biblical texts, and Christian teachings, doctrines and practices is central to my research and teaching.

How do you think The Shiloh Project’s work on religion and rape culture can add to discussion about gender activism today?

Rape culture and ideology can be insidious; that’s part of its power. One way to dismantle its power and the shame and guilt it perpetuates is to name it, as we saw with #MeToo. During that campaign, I was really struck, moved, and enraged by the shared stories of my friends and colleagues who had experienced harassment in academia: at conferences, in meetings, when travelling, and at University or departmental social events. It was also painful to see how many social media posts by women about #MeToo started with a line or two saying that they didn’t think what they’d experienced was ‘serious’ enough to warrant mentioning; and the media backlash against those testimonies reveals, again, the prominence of gendered violence and its acceptance. In a secularizing society like the UK, in which religion has lost some of its influence for individuals, communities and institutions, it is too easy and simplex to think that religion no longer shapes cultural norms. The work that the Shiloh Project does – the blogs, the lectures, the projects, the seminars, the research – is important research that uncovers religion’s role in constructing and supporting rape culture.

What’s next for your work with The Shiloh Project?

The project’s themes and aims are helping me think more critically about motherhood and rape culture. Just as Christianity’s essentialist ideas about women’s bodies limit their roles to the maternal, essentialist ideas underpin sexual domination and violence. Generally, though, I’m looking forward to potential joint projects and questions that are already emerging, to being part of a such a fantastic initiative, and learning with and from such a fantastic bunch of scholars.

And I really need to write my blog piece…

We interview Valerie Hobbs, Senior Lecturer in Linguistics at the University of Sheffield, on the ninth day of the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-based Violence campaign.

Tell us about yourself…who are you and what do you do?

My name is Valerie Hobbs, and I am a linguist at the University of Sheffield. I am one of those scholars who likes to do all sorts of things, but most of my research and teaching orbits around the areas of English for Specific Purposes, with a focus on religious language. In other words, I’m interested in how different groups of people use language in ways that suit their particular needs and goals.

How did you get involved in The Shiloh Project?

Katie Edwards, a friend and colleague at Sheffield, invited me along to a workshop on religion and rape culture in Leeds, where I met Johanna Stiebert, Caroline Blyth, Nechama Hadari, Emma Nagouse, and Jessica Keady. What impressed me about this group was the balance they strive for and achieve between diversity of perspectives and singular focus on examining and confronting the ways in which religion is used to incite and validate violence towards women. This is a group of scholars who unite around a shared interest and purpose but who invite discussion. In my experience, this is rare.

How does The Shiloh Project relate to your work?

A few years ago, I decided to take a break from work I was doing on language in philosophy and write a paper on a topic I’ve long been mulling over: how the conservative Christian church talks about feminism. This work prompted an invitation to attend the ecclesiastical trial of a pastor in the USA who refused to require his disabled wife to attend church. As a professing Christian, I was motivated by this experience to focus my work on issues that powerfully shape and affect religious women.

Since then, I have worked on, for example, Christian sermons on divorce, as a way to investigate the ways in which pastors (don’t) preach about domestic violence. Over the summer, I contributed a chapter based on this project to the series of volumes on Rape Culture and Religion, edited by Shiloh Project leaders Caroline Blyth and Katie Edwards along with Emily Colgan. I have plans for further projects on gender in sermons (since sermons are highly significant within the Christian context), but I’m also interested in hymns.

Then there is the activism that necessarily accompanies my scholarly work. I am grateful to have had opportunities to support Christian women who have endured various forms of violence by men in the church, including not only their spouses but also Christian leaders who too often use the Bible to minimize, excuse, and even justify physical and emotional abuse. Recent public-facing work stemming from these interactions has included, for example, a series on the ways in which church governments handle abuse cases. But I also spend time writing e-mails and letters and talking on the phone in an effort to support women whom men have abused.

How do you think The Shiloh Project’s work on religion and rape culture can add to discussion about gender activism today?

Faith and religion are an important source of identity and ideology for billions of people around the world. As a result, religious ideas are not confined to religious contexts but have made their way into all sorts of cultural contexts. Advertising, news media, and politics are just some of the places where we find traces of religion, and powerful players in society often deliberately draw on religion to attract followers.

In my view, one of The Shiloh Project’s most significant contributions to the discussion about gender activism are the ways in which it makes explicit these links between religion and cultural attitudes to gender roles. This involves examining the religious doctrine itself as well as how and where doctrine manifests itself in society. For example, the Shiloh Project’s Katie Edwards has done some ground-breaking work on the ways in which advertisers draw from the Creation account in Genesis and capitalize on common representations of Eve as seductress.

However, at the risk of sounding pessimistic, I think we must be modest in our ambitions to bring about change in society around us. While much work has been done on the issue of gender-based violence and discrimination, yet the problem persists and seems even more entrenched. We can easily grow discouraged. I’ve concluded that I must act on my convictions but resist being so arrogant as to think my work will even begin to fix what is wrong with the world. That runs counter to the message we get from academia these days, where we are encouraged to plan for and measure the impact of our research and rate our value accordingly. But I don’t believe impact is up to us. Instead, as I see it, at the heart of The Shiloh Project is simply this: love your neighbour. If society becomes any better as a result of anything we do, if we positively influence even one person who encounters our work, that is a great mercy.

What’s next for your work with The Shiloh Project?

I recently wrapped up my work on divorce sermons and hope to have another recently submitted paper on this project accepted for publication in the spring. I am now working on two other projects: language of discrimination in religious institutions and discourse of consent among popular Christian organizations. I’m also working on a proposal for a book which will draw on my work in these various areas. There is so much work to do and so little time! My Shiloh Project colleagues are doing all manner of funded projects, and it is inspiring to be surrounded by such driven academics.