We are thrilled to announce the full programme for our upcoming Religion and Rape Culture Conference.

You can access a waiting list for tickets here.

We are thrilled to announce the full programme for our upcoming Religion and Rape Culture Conference.

You can access a waiting list for tickets here.

Katie Edwards and David Tombs’ recent article in The Conversation (23 March 2018) draws on the earlier article David Tombs, ‘Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse’, Union Seminary Quarterly Review, 53 (Autumn 1999), pp. 89-109, available at Otago University Research Archive.

The article shows how reports of torture in Latin America reveal the role of state terror and prevalence of sexual abuse, and how these might help towards a closer reading of crucifixion.

Earlier this month Professor Linda Woodhead (University of Lancaster) wrote a comment piece for The Telegraph building on the work in The Conversation article. Read Woodhead’s piece here.

On March 31st 2018, CNN included David Tombs’ research in an article on Easter as a ‘#MeToo moment’. Read the CNN piece here.

On 5th April, the original article by Edwards and Tombs was translated into Indonesian.

Shiloh co-lead Katie Edwards has a powerful opinion piece in The Guardian of 21 March 2018. A longer version features in her Lent Talk for BBC Radio 4 (8.45pm) on the same day. A shorter version was repeated in Radio’s 4 Pick of the Day on Sunday 25th March 2018.

This piece gets to the heart of some of the topics central to the Shiloh Project: namely, how biblical texts can be used, usually very selectively – in this case highlighting the silent Jesus of Matthew to the exclusion of the vocal Jesus of John – in modern contexts – in this example Rotherham, which was at this time one of many locations throughout the UK where girls and women were being groomed for sexual abuse and exploitation and silenced when they tried again and again to report their abusers – with toxic effect.

The role of religion and the Bible is complex and ambiguous, as this personal account makes painfully clear.

See the advance review from The Times for details:

Many of our members (including our conference organising team) have been on strike over the last month as part of the UCU (University and College Union) industrial action over USS pensions. Over 60 universities in the UK are involved. Members of UCU continue to be on action short of a strike.

We are extending the call for papers deadline for our Religion and Rape Culture conference to 5pm March 29th.

See updated call for papers:

We are thrilled to announce our keynote speakers will be Professor Cheryl Exum and

Professor Rhiannon Graybill.

The Shiloh Project is a joint initiative set up by staff from the Universities of Sheffield, Leeds and Auckland (NZ) researching religion and rape culture. We are proud to announce a one day interdisciplinary conference exploring and showcasing research into the phenomenon of rape culture, both throughout history and within contemporary societies across the globe. In particular, we aim to investigate the complex and at times contentious relationships that exist between rape culture and religion, considering the various ways religion can both participate in and contest rape culture discourses and practices.

We are also interested in the multiple social identities that invariably intersect with rape culture, including gender, disabilities, sexuality, race and class. The Shiloh Project specialises in the field of Biblical Studies, but we also strongly encourage proposals relating to rape culture alongside other religious traditions, and issues relating to rape culture more broadly.

This conference is open to researchers at any level of study, and from any discipline. We invite submissions of abstracts no more than 300 words long and a short bio no later than 5pm March 29th. Please indicate whether your submission is for a poster or a presentation. We particularly welcome abstracts on the following topics:

Gender violence and the Bible

Gender, class and rape culture

Visual representations of biblical gender violence

Representations of rape culture in the media and popular culture

Teaching traumatic texts

Methods of reading for resistance and/or liberation

Sexual violence in schools and Higher Education

Religion, rape culture and the gothic/horror genre

Spiritualities and transphobia

Familial relations and the Bible

For more information, or to submit an abstract, email shiloh@sheffield.ac.uk

Booking is now open for our Religion and Rape Culture Conference. Places are limited so book your ticket fast!

Please note that we have small travel bursaries to contribute to travel costs for UK students who wish to attend the conference. These bursaries will be awarded on a needs basis, and speakers/those with poster submissions will also be prioritised.

The deadline for submission of proposals for our Religion and Rape Culture Conference is fast approaching! Get your proposals in by 19th March 2018. See the CFP below for more details.

Email shiloh@sheffield.ac.uk for more information.

Here is the second in our occasional series profiling lesser known NGOs doing important work that addresses – sometimes directly, sometimes less directly – sexual violence and gender-based inequality. In the first instalment we heard from Carrie Pemberton Ford about her organisation’s work in the area of human trafficking (read about it here).

This time we hear from none other than my wonderful niece, Antonia McGrath. Straight out of high school, aged 18, Antonia went to spend a year in Honduras working in an orphanage. The experience influenced her profoundly and moved her to co-found an NGO. She has returned to Honduras regularly and has also given motivational talks. A student of International Studies, she is applying her experiential and academic knowledge for a greater good.

Please read about Antonia and the NGO and please help promote educate! There is a link below for making contact directly, as well as for making financial contributions, which are gratefully received and put to excellent use, directly in Honduras: every single dollar and pound. See if you can watch this short, beautiful and powerful film and not donate.

____________________________________________________________________________

Tell us about your NGO and your own role!

My name is Antonia McGrath and I’m a student in the Netherlands, studying International Studies with a specialization in Latin America. I’m also the co-founder and chair of a small non-profit called educate. that works to empower children and youth in Honduras through education and preventative healthcare.

educate. was started by myself and a close friend of mine called Lisa. We both lived and worked in Honduras for a year after we finished high school, and later both ended up studying in the Netherlands. We were both deeply impacted by our experiences and the people we’d met and we had countless conversations and ideas about possible projects we could organise. Eventually, we looked up how to start a charity, and eight months later educate. got registered in Scotland! We now have a board of five directors, all of us university students who work on a voluntary basis, and a growing group of volunteer members who work in a variety of roles. In Honduras, we also have three Project Leaders and a Cultural Advisor, all of whom also work on a voluntary basis.

As an organisation, we’re driven by the belief that education is what lies at the root of sustainable development, and that by providing young Hondurans with opportunities to continue studying, as well as improving the quality of the education they receive, we can make small but significant changes to the immense levels of poverty and inequality that exist in Honduras.

Our main focus is a scholarship programme to allow excellent but underprivileged students to continue their education to the university level. We’re currently supporting two young women from rural communities at universities in Honduras. Stephanie, whose parents are farmers, is studying to become a doctor, and Tania, whose grandfather’s job as a shoemaker makes up the formal income of the entire family, is studying to become an industrial engineer. For both of these young women, this is an opportunity they would not have had without the scholarship. At the moment, we aim to take on one additional scholarship candidate every year. We also run projects at underfunded schools and orphanages around the country, including funding an animal therapy programme and several libraries.

It’s incredibly hard work, but everyone in our team is so dedicated and driven, and the impact that we’re having, even though on a grand scale it might seem insignificant, is completely life-changing for the individuals it affects, which makes it incredibly rewarding.

The Shiloh Project explores the intersections between, on the one hand, rape culture, and, on the other, religion. On some of our subsidiary projects we work together with third-sector organisations (including NGOs and FBOs). We also want to raise awareness and address and resist rape culture manifestations and gender-based violence directly. We’re interested to hear your answers to the following:

How do you see religion having impact on the setting where you are working – and how do you perceive that impact? Tell us about some of your encounters.

Religion is incredibly important in Honduras and influences almost all aspects of life. As an organisation, we have no religious or political affiliation, but the presence of religion in Honduras definitely impacts our work – helping in some ways, and hindering in others. Like I said, educate. has no religious affiliation, so I speak here solely based on my own personal views (and, perhaps it is important to mention, I too have no religious beliefs. In fact, I consider myself an atheist).

While Catholicism is still the dominant religion, Honduras is now one of the most Protestant countries in Latin America – largely due to the increased presence of evangelical missionaries in the country. In my experience, people extract great value from what you state as your religious persuasion and your stance creates a picture for them of your core beliefs and the specific ideas and stereotypes that are attached to these in Honduras. A friend, when I told him I was atheist, once said to me: “you’re not atheist, you’re a good person!” In such a religious society, labelling myself as an atheist often requires a great deal of backpedalling to take away people’s suspicions towards me and to prove that I do in fact have morals, despite not being religious.

Where I lived on the north coast, near San Pedro Sula, there’s quite a divide between Catholics and “Christians” (by which they mean Evangelicals and other Protestants). This divide creates a lot of animosity in some communities. “Evangelicals think their ideology is superior, and they look down on the Catholics,” says a good friend of mine in Honduras who says he’s agnostic, “but really the Catholics are just as bad, they’re just more discreet about it.” In a conversation I had with several Evangelicals, they blamed Catholics for Honduras’ problems with HIV/AIDS and gang violence.

The religious divide can clearly be seen through small daily interactions with people. A taxi driver once casually spent the taxi ride telling me how “when I was Catholic I used to dance and drink, but I would never do such devilish activities and be around such sinful people now that I have seen God’s true light.” Another time, I was picking up a Western Union money transfer at the local bank and the lady allowed me to collect my money without showing the proper identification, due to the fact that she had seen me at the local Evangelical church once with my boss, meaning I was an upstanding member of the community. These small interactions are telling, and show, with the utmost bluntness, the complete polarisation of these two religious groups.

I have seen both some incredibly impactful and some shockingly harmful work being done by religious groups in Honduras. The Catholic Church in San Pedro Sula does some amazing work with street children and returning migrants, which I spent many hours discussing with the Priest and the Cardinal on various trips into the city. But not all of the religious work in Honduras is positive. Many seemingly-positive religious projects become murkier and darker once you get inside them. There are definitely people that come and use the Bible as a weapon – “believe this, and we’ll help you.” Or people who take in children and force them to conform to their religious beliefs and violently punish them if they don’t – I have personally witnessed things like this and have been deeply disturbed by the irony of the link between religion and this kind of behaviour.

Despite the divisions it created, I also saw religion to be an extremely important uniting force, especially in poor communities. In these areas, religion and faith provided an incredibly powerful sense of community and ideology to help people get through hard times.

educate.’s lack of religious affiliations has not created any problems for us in Honduras, and we have and continue to work successfully with organisations and individuals from many different religious backgrounds and persuasions. Personally, I think our lack of religious affiliation possibly affords us more respect as an international body outside of Honduras, as we do not base our projects or our funding on religious ideas. Nevertheless, we remain aware of and respect the presence and importance of religion in the lives of our beneficiaries and members of our Honduras team.

How do you understand ‘rape culture’ and do you think it can be resisted or detoxified? How does the term apply to the setting where you are working?

Rape culture, in my understanding, refers to the culture of normalization of sexual harassment and assault, the stereotypes that surround gender and sexuality, and the pervasiveness of sexual and gender-based violence that ensues from this.

Rape culture is definitely very prevalent in Honduras. As in much of Latin America, there is a strong culture of machismo in Honduras. Men are expected to be strong and “masculine” – tough and chauvinistic, whereas women usually take on a role that is much more submissive and “feminine.” Machismo also has relevance to sexual culture. Men prove their manliness by being sexually dominant, and they have a sexual appetite that they have the “right” to satisfy, while women have a much more passive role and are less in control. Honduran gender roles within the home present the woman as the matriarch: la jefa (“the boss”). However, this philosophy is centred only within family boundaries, and in wider society, it is expected for women to take on a much more submissive role.

An obvious symptom of machismo culture is the ever-popular music genre of reggaeton, which is played everywhere from the public buses to city streets, bars, salons, supermarkets and on the radio. It’s a genre that is notoriously derogatory and objectifying towards women, with a high degree of focus on male entitlement and disregard for women’s autonomy over their bodies. While reggaeton is certainly not unique as a music genre in its degradation of women, the level of this is extreme, and the popularity of this music normalizes this attitude of male dominance over women in wider society. The fact that young children grow up seeing music videos on buses with women portrayed in a blatantly sexual manner while men clearly show their dominance over these women, makes this attitude of male dominance truly a part of their upbringing. Of course, this is just one example of machista culture at work in Honduras.

A key aspect of rape culture in Honduras, and one that is truly shocking, is the extraordinarily high rate of femicide, with one femicide every 16 hours. Since 2014, the United Nations has reported that 95% of cases of sexual violence and femicide in Honduras were never investigated, and only 2.5% of cases of domestic violence were settled. The threat of violence towards Honduran women is very real and constant.

Forced child marriage is also still common in rural areas in Honduras, having been legally banned only last year, and young girls are often married to much older men without their consent. The consequences of this are huge, with these girls dropping out of school and being forced into non-consensual relationships that often result in early pregnancy, which not only impacts their future but can also cause medical problems as young girls’ bodies are often not physically ready for the demands of pregnancy and childbirth.

The sex industry in Honduras is also a huge problem. At a children’s home in Honduras where I used to work, a young girl told me about how she had provided sexual services for much older men to make money for her family. She was nine when she told me this, but the incidents she described had happened four years earlier. Another time, when I was interviewing various individuals as part of a documentary about Honduras’ migration crisis, numerous teenage girls opened up about horrific stories of rape, often at the hands of their own family members – fathers, uncles, brothers. This is not uncommon.

I think the main ways that rape culture can be combated are through educating people, particularly children and youth, about consent and what that means, teaching individuals about their rights and highlighting that these are not drawn along gender lines, challenging concepts of masculinity and femininity, recognizing problems in the media, churches and communities and working to challenge and change them, and creating policies and programmes that support survivors and victims of rape culture instead of blaming them.

Discussions must take place to highlight to children and youth, and the wider community, that sexual and emotional violence and abuse needs to be reported. Adult men/women referring to an underaged child as sexually desirable due to the fact she/he looks older than their biological age is currently socially acceptable, but this must change. The same is true of expressing that daughters/sons are bringing shame to their families by “tempting people,” when in fact the people they are “tempting” are the problem. Or the pervasive notion that it is a woman’s duty to respond to a catcaller. Or the fact it is unheard of for a Honduran woman to walk alone at night without fearing or facing sexual assault. That to put yourself on the streets or in a situation or area after dark is putting your body on a plate. Accusing the prostitutes on the street of being whores and without morals, yet not breathing a word about the married men who use their services, with one hundred words for a prostitute and barely one for the client. The motel and brothel owners can walk without shame in their communities while the prostitutes are ostracized. These ideas and cultural norms must be discussed and fought against in order to combat and detoxify rape culture in Honduras.

As a white woman who is not from Honduras, I recognize that my perspective is different from that of a Honduran woman and that I cannot truly know how rape culture in Honduras affects Hondurans. Certainly, when I was living in Honduras, and on the occasions that I have gone back to visit, I experienced harassment on the streets and saw, as an outsider, the ways in which men and women relate to one another and what the societal expectations were for each of them. But I cannot claim to have been truly a part of that world. As a white woman, my skin colour affords me some protection (kill a Honduran and no one will ask questions, but kill a tourist and it’ll be on international news), but I still felt unsafe walking at night without being accompanied by a man. It is impossible, on such an intricately complex topic, to claim to understand the lived experiences of Honduran women, because I have never, and will never, experience these first hand.

Speaking to a close friend in Honduras about this topic, he told me that he is worried about raising his daughter in such machista culture. “Women face a lot of physical threats,” he says, “but I think it’s the psychological damage that this culture has that is most detrimental. I want my daughter to believe that she is important, and that she can do anything. I don’t want her to be scared to live her life the way she wants to.”

Does your project encounter or address gender-based violence and inequality? Tell us how.

Gender-based violence and inequality are not explicitly part of our mission, but they definitely play a role in our work. While we don’t support only girls, both our current university scholarship recipients are young women studying to become an engineer and a doctor. Simply by supporting them, we are facilitating the process for them to become role models in their communities to younger girls, and this naturally contributes to breaking down norms and expectations in society and creates a platform to change gender-based inequalities. With a university degree, the young women we support gain not only an education that changes their life and the opportunities available to them, it also impacts their families and communities.

How could those interested find out more about your NGO? How can people contribute and where will their money go?

We have a website (educate-ngo.com) where there’s lots more information about us and our work, so that’s the main place where people can find out more about us. There’s a blog on the website where we post updates every month or so, but for more immediate updates, there’s our Facebook page (www.facebook.com/educatengo).

On our website there is a link to a donation page. We really appreciate every single donation we receive, and all of them go to making real, tangible impact in individuals’ lives, either through scholarships or through projects at schools and orphanages. Because we’re such a small organization, you can see exactly where your money is going. We all work on a voluntary basis and strive to keep you regularly updated with photos, videos and articles on all of our projects.

We also have a contact page on our website, so for anyone who has questions or who is interested in getting involved, send us a message!

What kinds of posts would you like to see on The Shiloh Project blog and what kinds of resources that come into our orbit would be of value to you?

Katie Edwards, University of Sheffield and M J C Warren, University of Sheffield

It is the start of Lent, a time when Christians reflect on the upcoming Passion of Jesus. Jesus is held up as an example of steadfastness in the face of oppression by malevolent forces. He shows strength through his silence, approaching his suffering willingly.

Throughout the ongoing #MeToo movement Jesus has been invoked by Christian communities as a co-sufferer and promoted as a model for redemptive suffering, particularly in the face of abuse. But is Jesus’s silence a troubling model for victims of sexual assault?

One of the hallmarks of Jesus’s portrayal in popular culture is his silence in the face of Pontius Pilate’s interrogation. This image of silence comes from the three Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke’s versions of Jesus’s trial.

When Jesus does speak, his words are brief, cryptic, and taken from the Gospel of John rather than the other three, where Jesus’s silence is emphasised.

In Matthew and in Mark, the entire trial scene takes place in four verses; in Luke, where there is slightly more input from “the multitudes” as well as a second trial in front of Herod, we are done in eight verses. Even so, in these gospels, Jesus makes no answer to the charges laid against him.

It’s likely that Matthew, Mark and Luke’s versions depict Jesus’s silence as a way of characterising him as the “Suffering Servant” of Isaiah 53:7. In each case, whether in these gospels or in Isaiah, the image portrayed is one of virtue in silence, and of a pious sacrifice in the face of an unjust world. It is that silence that ultimately kills him.

This contrasts with John’s depiction of the same scene, which takes place over ten verses, more than double the amount of text devoted to the trial in Mark and Matthew’s versions. In John, Jesus is clear about who he is and makes a direct response to accusations; he also corrects Pilate’s misunderstanding about his true identity. This is part of Jesus’ plan – he is clear about his death being the will of God his Father.

But whether he is silent as in Mark or whether he speaks in his own defence as in John, Jesus is sentenced to death and crucified. The end result – suffering, pain, and death – is the same.

Parallels have been drawn between Jesus’s response to his abuse during the Passion and the #MeToo movement. Not least because, like Jesus, the victims of Harvey Weinstein’s alleged abuse have been condemned whether they’ve spoken out or remained silent.

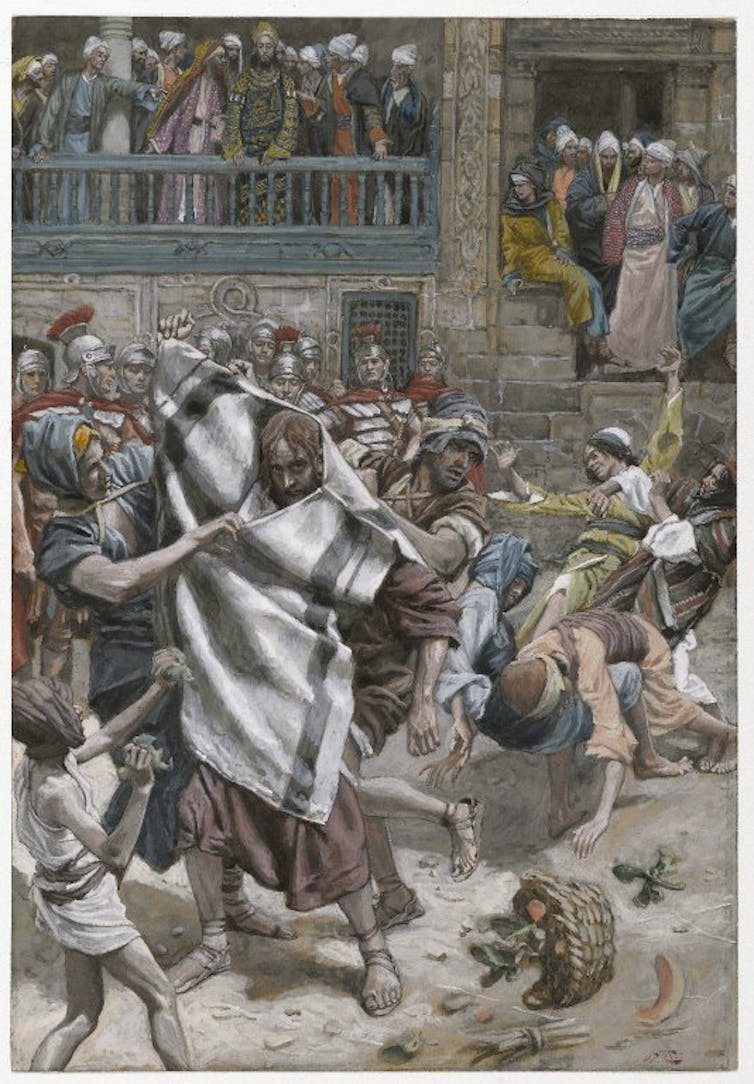

While the torture and crucifixion of Jesus in the Bible is widely accepted, the idea that his abuse included sexual assault is a less established aspect of the Passion narrative.

The work of David Tombs at the University of Otago shows that Jesus’s torture included a sexual element. According to the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus is stripped three times and his nakedness is part of his humiliation. Similarly, biblical scholar Wil Gafney has suggested that the crucifixion of Jesus is a form of sexual assault:

I consider … the full range of torture and humiliation to which Jesus of Nazareth was subjected, physical and sexual. The latter is so traumatising for the Church that we have covered it up – literally – covering Jesus’ genitals on our crucifixes … The mocking, taunting, forced stripping of Jesus was a sexual assault. He was, as so many of us are – women and men, children and adult – vulnerable to those who used physical force against him in whatever way they chose.

Throughout the ages, Jesus has been presented as a model of suffering. For instance, in the 18th century, St Paul of the Cross declared that:

The more deeply the cross penetrates, the better; the more deprived of consolation that your suffering is, the purer it will be; the more creatures oppose us, the more closely shall we be united to God.

Silence in the face of abuse, sexual assault and violence, then, becomes glorified and dignified. Some Christian communities have recognised the problems in constructing silence in the face of abuse as virtuous and have taken steps to challenge it.

For example, the hashtags #SilenceisNotSpiritual and #ChurchToo have been developed to offer a counter-narrative to the idea that silent suffering is an emulation of Jesus.

But the backlash to these hashtags, which promote the voices of those who’ve experienced sexual abuse and violence, has included some more troubling connections between Jesus and the #MeToo movement. Some social media commentators have presented Jesus as the perpetrator of sexual assault rather than as the victim.

By using sexual assault as a metaphor for Christ taking Christians by force, penetrating their sin with his righteousness, this view presents Jesus as a perpetrator of sexual assault, undermining the experience of survivors and victims of sexual violence and suggesting that sexual assault might be a potentially positive (or even necessary) experience.

The reaction to Jesus’s silence as well as his self-advocacy presents a troubling model for those who view Jesus as an exemplary victim of abuse, since both silence and speaking out lead to further pain and violence.

![]() This should lead to an interrogation of how we as a society value suffering and especially silent suffering in the wake of #MeToo, but also challenges the notion that victims are obligated to speak out in order to be vindicated. In the end, the blame should still fall firmly on the abusers.

This should lead to an interrogation of how we as a society value suffering and especially silent suffering in the wake of #MeToo, but also challenges the notion that victims are obligated to speak out in order to be vindicated. In the end, the blame should still fall firmly on the abusers.

Katie Edwards, Director SIIBS, University of Sheffield and M J C Warren, Lecturer in Biblical and Religious Studies, University of Sheffield

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

It’s Sexual Abuse and Sexual Violence Awareness Week! This will be followed from 14. February by the One Billion Rising Campaign. Between 14 February and International Women’s Day, on 8 March: look out for regular Shiloh Project updates!

Today, during Sexual Abuse and Sexual Violence Awareness Week is a good time for The Shiloh Project to launch the first post of an occasional series profiling NGOs working actively against rape culture in its myriad forms.

Organizations such as Women’s Shelter and Rape Crisis are very well known and do fantastic and important work. The NGOs we’ll be profiling here are less well known and also important to support, promote and celebrate. First up today is The Cambridge Centre for Applied Research in Human Trafficking, introduced by its Development Director, Rev. Carrie Pemberton Ford …

Tell us about your NGO and your own role.

My name is Carrie Pemberton Ford. I am an Anglican priest and academic, as well as Development Director of the Cambridge Centre for Applied Research in Human Trafficking (CCARHT). The Centre is based in Cambridge (UK). CCARHT is a nonprofit (or not-for-profit) Community Interest Company (CIC), which has Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) recognition from the United Nations office working on counter trafficking.

CCARHT’s vision is to foster applied research that addresses the contemporary global scourge of Human Trafficking, as well as to set this scourge in the wider context of social justice, gender equity, international economic and political power distribution, safer migration and asylum corridors, voice and victim empowerment, and multi-partner co-operation. Human trafficking, as defined by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is the ‘hydra-headed monster’ manifesting in multiple forms that we seek to defeat. This is in line with the Palermo Protocols: three protocols adopted by the United Nations to supplement the 2000 Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. Two of these protocols address human trafficking: one is aimed at suppressing and punishing the trafficking of persons, especially women and children; the second addresses the smuggling of migrants by land, sea and air.

The Shiloh Project explores the intersections between, on the one hand, rape culture, and, on the other, religion. On some of our subsidiary projects we work together with third-sector organizations (including NGOs and FBOs). We also want to raise awareness about and address and resist rape culture manifestations and gender-based violence directly. We’re interested to hear your answers to the following:

How did you get involved in the work you are doing? Do you see religion having impact on the setting where you are working – and how do you perceive that impact?

I was involved in developing victim care responses to human trafficking before the Palermo Protocols became ratified by the UK Government (in 2003). I was the founder of the UK Charity Churches Alert to Sex Trafficking across Europe (CHASTE), and the instigator of the NOT FOR SALE campaign, which raises the issue of the commodification of female lives, along with a minority culture of male lives, within the sex industry. This was my entry into the last fifteen years of working in resistance to human trafficking – in its widest interpretation, which involves labour trafficking (or, slavery), child exploitation, organ trafficking, gamete trafficking and surrogacy, alongside trafficking for sexual exploitation and child abuse within the pornography ‘industry’.

The role of religion is extremely compromised and complex in the challenge of human trafficking. On the one hand, those of us whose faith discourse developed within a culture that values human liberation, gender equality and human rights, recognize religious communities as having powerful potential to interrupt and begin to dismantle cultures of commodification, devaluation of the ‘divine image’ imprint of humanity, and gender-based and racial hierarchies, alongside also age-related abuse, which runs as a major vein across human trafficking and modern slavery. On the other hand, many of these discourses have had long and embarrassing support from patriarchal and systematized ‘canonical’ teachings and their organizational realization.

Consequently, the role of religion is profoundly ambiguous, but offers some dynamic opportunities to address the diverse challenges around human trafficking – from the articulations of state interests, as well as some global conversations around international distribution of resources, value chains, and ensuring safe corridors for the movement of people – all of which address international trafficking – whilst also exploring community accountability, social justice and rape cultures within the domestic and national space.

Whether positive or negative, the role and impact of religion cannot and should not be ignored – including in terms of understanding the full picture of human trafficking.

How do you understand ‘rape culture’ and do you think it can be resisted or detoxified?

Rape culture is about the failure of interpersonal respect and the dereliction of an understanding of gendered difference founded on radical human equality. Rape culture underpins or is underpinned by political and economic hierarchies where the active consent of the other becomes void. Though its etymological background lies in the 1970s feminist movement, with a specific focus on ‘outing’ the ways in which society blames victims of sexual assault and normalizes male sexual violence, rape culture exists up until today and is fed by every societal message where one gender, ethnicity, class, ability, or sexuality becomes dominant and ‘entitled’ to transgress the embodied boundaries of the other.

Rape culture is resisted and detoxified through the raising up of equality, equity, and personal autonomy as rights protected by the State for all its citizens, by the enactment of the United Nations’ inalienable rights (as defined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948), and wherever religious discourse privileges this way of viewing humanity over and against the hierarchical forms which have so often dominated western and other cultures.

Sex trafficking is one form of human trafficking and directly indicative of rape culture. It violates fundamental human rights and human dignity and generates illicit finance for the pimps and traffickers complicit in each and every delivery of a female, male or transgender person into the regional, national or international ‘sex market’. It feeds off the normalization of rape culture whereby the ‘consumer’ does not perceive their transaction as anything other than a ‘purchase’, consent having allegedly been delivered by the agreement to ‘exchange’ a body or bodily service for money.

The relationship between sex trafficking and prostitution more generally is important to disentangle. Important here is the recent and incisive work of Julie Bindel. Her book The Pimping of Prostitution offers some clear insights into the multiple tiers implicit in the notion of ‘consent’ within the context of the global sex industry. She also highlights how the dominant culture refuses to explore the profound power asymmetries present in the embodied politics of this ‘market’ exchange, where the golden mean of the market is rigged by profound systemic inequalities in terms of gender, ethnicity and class.

These matters inform some of the challenges religious discourse needs to address going forward. CCARHT has already developed a theological wing to our work to explore such challenges.

How could those who are interested find out more about your NGO? How can people contribute and where will their money go?

For information and resources, please see the CCARHT website.

We host an annual symposium, which this year is held at Cambridge University from 2nd – 6th July 2018. Our focus will be ‘Terror, Trauma and Transport’. We are hoping to spend the final day of the conference on the theological explorations underpinning the Shiloh Project. (It would be wonderful to attend your conference on 6th July – but that might be difficult, logistically!)

We are also co-curating a summer school on ‘Migrants, Human Rights and Democracy’, to be held in Palermo (Sicily) from June 11th –15th June 2018.

Another upcoming event is a mini conference to be held in London on 13th April. The focus of this is very relevant to the Shiloh Project: namely, the multi-faceted issues and dimensions surrounding the safeguarding and protection of spouses and children in the context of domestic abuse, with particular focus on the roles played by coercive control or institutional inertia of clergy and religious institutions. (Please see: #Hometruths and #Badfaithed or contact me: Carrie@Badfaithed.org)

CCARHT is a not-for-profit organization, and all donations go towards financing publications, mini symposia, research and at-risk-community interventions. These currently involve work in all of Sicily, Catalonia, Macedonia, Ukraine, and the UK.

All our work is focused on developing effective and more sustainable counter-human-trafficking interventions. In the course of this, we look, for example, at international and inter-regional economic fractures, the nexus with migration, creating asylum delivery, victim protection and survivor care, entrepreneurial empowerment for survivors, averting risky behaviours and situations for communities working with unaccompanied minors, supply chain transparency and value chain transformation.

We rely on fee-paying participation of our training symposia, on commissioned reports and donations for the business intervention and training work we are currently undertaking in Sicily, and on co-sponsored arts interventions – the most recent being #Justsex. We are currently seeking £8,000 to develop #Justsex materials to support the ‘Physical Theatre’ work which is currently beginning to find access into School PSHE (Personal and Social Health Education) programmes. (Please contact me directly for more details!)

Please see our library page on www.ccarht.org for our latest reports including our recent submission on ‘Behind Closed Doors: Addressing Human Trafficking, Servitude and Domestic Abuse Through the Black African Churches in London’, which has resulted in the development of a new charity from the cluster working on precisely these issues – namely, ‘Seraphs Tackling Social Injustice’.

What kinds of posts would you like to see on The Shiloh Project blog and what kinds of resources that come into our orbit would be of value to you?

Anything around the way in which rape culture, or patriarchal thinking, or pre-emptive demolition of consent, or gang formation and criminality, works internationally, and cross-culturally, as well as how rape culture is implicitly supported through some religious structures and discourses – and also how rape culture can start to be dismantled through a liberation theology or through a breach in rape culture-supportive theological praxis.

Religion and Rape Culture Conference

We are delighted to announce a one day interdisciplinary conference exploring and showcasing research into the phenomenon of rape culture, both throughout history and within contemporary societies across the globe. In particular, we aim to investigate the complex and at times contentious relationships that exist between rape culture and religion, considering the various ways religion can both participate in and contest rape culture discourses and practices.

We are also interested in the multiple social identities that invariably intersect with rape culture, including gender, disabilities, sexuality, race and class. The Shiloh Project specialises in the field of Biblical Studies, but we also strongly encourage proposals relating to rape culture alongside other religious traditions, and issues relating to rape culture more broadly.

This conference is open to researchers at any level of study, and from any discipline. We invite submissions of abstracts no more than 300 words long and a short bio no later than 19th March. Please indicate whether your submission is for a poster or a presentation. We particularly welcome abstracts on the following topics:

For more information, or to submit an abstract, email shiloh@sheffield.ac.uk