Today we celebrate calling out – but that needs a bit of qualification and explanation.

‘Calling out’ refers to a direct challenge to what someone has said or done. Usually, ‘calling out’ is performed publicly, including (indeed very often) on social media. The intention of calling out is to confront and to expose someone, or something.

Calling out can be, or can get, nasty; it can escalate; and sometimes it can expose the caller outer as hypocritical, or attention-seeking, or band-wagoning.

But calling out can also be a registration of protest, an on-the-spot expression that something is wrong and needs to change. It can be a first and decisive and vocal step in a process of tackling wrongs.

Let’s face it, we have had some big wake-up calls, including in academia, showing up that very many things have been rotten for too long. Sexual harassment and abuse on campuses, to give just one example, have been rampant, and often ignored, or tacitly, or resignedly, accepted. Processes for addressing sexual harassment and abuse, meanwhile, are often ineffectual. (For some careful investigative work on this topic by Al Jazeera, see ‘Degrees of Abuse’, here). Other kinds of bullying, systemic inequality, discrimination, and abuse are also entrenched.

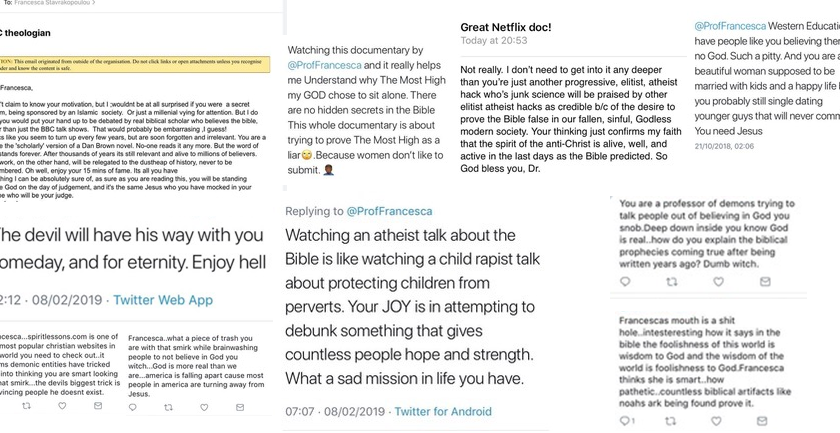

This year, the Shiloh Project hosted the pushback series to give a platform to speaking up about some of the things that are wrong in academia. We heard from an anonymous feminist scholar who eventually left, defeated, the conservative theological college where she had worked for multiple years. We heard also from Pauline scholar Grace Emmett, Buddhism scholars Amy Langenberg and Ann Gleig, theologian Karen O’Donnell, Hebrew Bible scholar Francesca Stavrakopoulou, and our own co-director Chris Greenough. Each spoke—if sometimes with caution and trepidation, mindful of how risky it can be to speak up or call out—of how they have been undermined and thwarted, intimidated, and maligned, in response to their research, often by other academics.

We also published a response to the ‘I’m back!’ statement of Jan Joosten, which he wrote shortly after completing his sentence. Joosten’s statement elicited many indignant Twitter comments from biblical scholars and, not long after, a panel discussion with the title ‘The Ethics of Citation: Sexual Abusers in Biblical Studies’. This panel comprised Stephen Young, Emily Schmidt, and Mark Leuchter, and was chaired by Meredith Warren (see here). The discussion covers a range of people, offences, and situations, and is largely exploratory. It asks, ‘is it ethical to cite sexual abusers?’

It is, I agree, important to think about this question. But it is not in every case straightforward to answer with either an unqualified ‘yes’ or an unqualified ‘no’. Where Joosten is concerned, I, for one, will not be citing him any time soon. I have cited Joosten in the past, prior to his conviction (see my earlier post, here). I will not cite his scholarship now, for two reasons. The first reason is that since Joosten was found guilty by a court of law for dreadful crimes on a large scale and this became public, I see him first and foremost as a sex offender. For me, this now overshadows any admiration, or respect I may have had for his scholarship in the past. When I see his name now, the first thing I think of is not his erudition, but that 28,000 items of violent child pornography were found in his possession. The second reason is that I see no signs of any attempts at reparation or restorative justice in Joosten’s statement.

There are still questions I grapple with and that the panel discussion—which rightly shifts focus to victims and survivors and calls out and condemns sexual abusers—doesn’t probe fully. How responsible are we as readers for background checking authors we cite? Is hearsay ever a legitimate basis, or only conviction? Does not citing apply only to authors convicted of sexual abuses, and if so, why? Why not authors guilty of other abuses, too, like environmental destruction, drug dealing, armed robbery, business malpractices… because these crimes also have grave consequences. Do we declare all our own privileges and detriments? Do we not cite the work of scholars if they are known to hold views we object to (e.g. on matters of sexual orientation and gender identity, on abortion or Zionism), even if they or we are writing on entirely other topics? I find myself still contending with some of these questions. And I will continue to contend with them, because they matter to me.

I also grapple with how the discussion about those convicted of sexual abuse can move forward, because the idea that anyone and everyone ever convicted of a grave offence is evermore excluded, also does not sit easy with me. What if they contribute to reparative programmes determined by survivors, for instance? Or what if they participate in restorative justice initiatives, where survivors receive a direct apology? In other words, calling out and openly identifying a misdeed or a crime is important—but it is not and should not be the end to it.

Back in 2019, Barack Obama spoke about ‘call-out culture’ and how calling someone out for something they did or didn’t do, and then sitting back, is not activism. As he went on to say, ‘the world is messy’ and ‘there are ambiguities’. There’s more to do and it’s not straightforward.

Calling out matters. Being called out can make us more aware. But, ideally, calling out opens up, rather than concludes, engagement. It’s only in the opening up that activism can flourish.