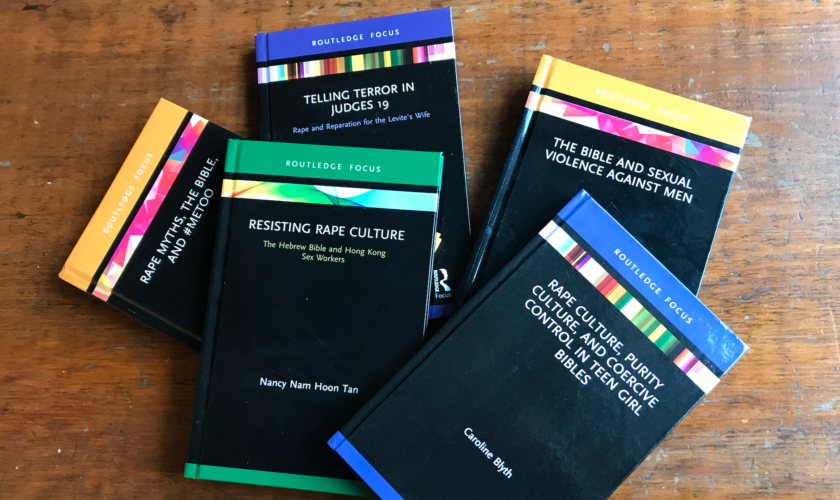

It’s just over a year since we launched our Bible and Violence project. With a list of over 120 stellar chapters, The Bible and Violence will be an inclusive reference work that explores the complex dynamics between the Bible, its interpretation, reception, and outworkings, with particular emphasis on violence in its multifarious forms.

We’re so excited to share the good news with you. The Bible and Violence project will be holding an online conference from Monday 25th – Wednesday 27th March 2024. The aim of this short conference is to share some of the work already submitted by contributors – to give you a sneak preview of the varieties of violence in biblical books and their uses.

Our fabulous line up of speakers and topics is below. Please note all times are GMT (UK), so please check for your local time equivalent.

The event is free, but please follow this link to sign up. Places are limited, so don’t miss out.

For any queries, please contact: thebibleandviolence@gmail.com

| Monday 25th March | ||

| 9:15-9:30 | Welcome | |

| 9:30-10:15 | Erin Hutton, Australian College of Theology, Australia | Striking like the Morning Star: How can Song of Songs 6:4–10 prevent domestic abuse? |

| 10:15-11:00 | Grace Smith, University of Divinity, Australia | Rape Culture and the Bible: the efficiency of rape and rape propaganda |

| 11:00-11:15 | Break | |

| 11:15-12:00 | Robert Kuloba, Kyambogo University, Uganda | The Ideological Dilemma of Suicide in Uganda: African Bible Hermeneutical Perspectives |

| 12:00-12:45 | Deborah Kahn-Harris, Leo Baeck College, UK | Violence in the Book of Lamentations |

| 12:45-13:00 | Close | |

| Tuesday 26th March | ||

| 14:00-14:15 | Welcome | |

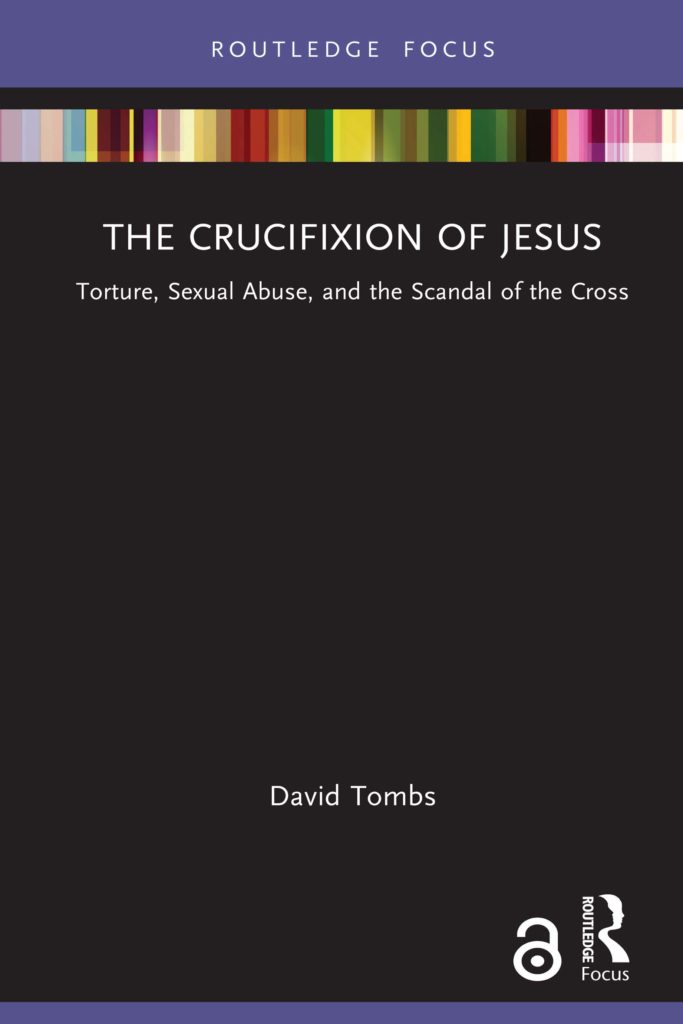

| 14:15-15:00 | Stephen Moore, The Theological School, Drew University, USA | Violence Visible and Invisible in the Synoptic Gospels |

| 15:00-15:45 | Juliana Claassens, Stellenbosch University, South Africa | Exploring Literary Representations of Violence in Bible in/and Literature |

| 15:45-16:00 | Break | |

| 16:00-16:45 | Barbara Thiede, UNC-Charlotte, USA | Violence in the David Narrative: A Divine Order |

| 16:45-17:30 | Alex Clare-Young, Westminster College, Cambridge Theological Federation, UK | The Bible and Transphobia: The Violence of Binarism |

| 17:30-17:45 | Close | |

| Wednesday 27th March | ||

| 14:00-14:15 | Welcome | |

| 14:15-15:00 | Alexiana Fry, University of Copenhagen, Denmark | Violence, Trauma, and the Bible |

| 15:00-15:45 | Susannah Cornwall, University of Exeter, UK | The Bible, Intersex Being and (Biomedical) Violence |

| 15:45-16:00 | Break | |

| 16:00-16:45 | Lena-Sofia Tiemeyer, ALT School of Theology, Sweden | Violence and Lack of Violence in the Reception of David |

| 16:45-17:30 | Luis Quiñones-Román, University of Edinburgh, UK | Divine Violence in The General Letters |

| 17:30-17:45 | Close | |