Please read all about M2M – Misogynoir to Mishpat.

You are invited to the project’s inaugural seminar in the series ‘Decolonizing God’ by Prof. Esther Mombo. The title is: Decolonizing God: African Women’s Epistemic Challenges to Patriarchal Jesus.

This event has now been rescheduled for Thursday 13 May, 16:00-17:30h. Please join via this Teams link.

Launch of the MISOGYNOIR TO MISHPAT RESEARCH NETWORK, and of the seminar series “Decolonising God” (organiser: CRPL Fellow Dr C.L. Nash).

1) Dr CL Nash, tell us a little bit about who you are, and what drives you. Also, what is M2M, which you’ve launched recently?

I am a woman from the U.S. and an independent scholar at the Centre for Religion and Public Life of the University of Leeds, where I manage two research projects. One project deals with religiously ensconced nationalism; and the other, amplifies the religious epistemologies of women of African descent.

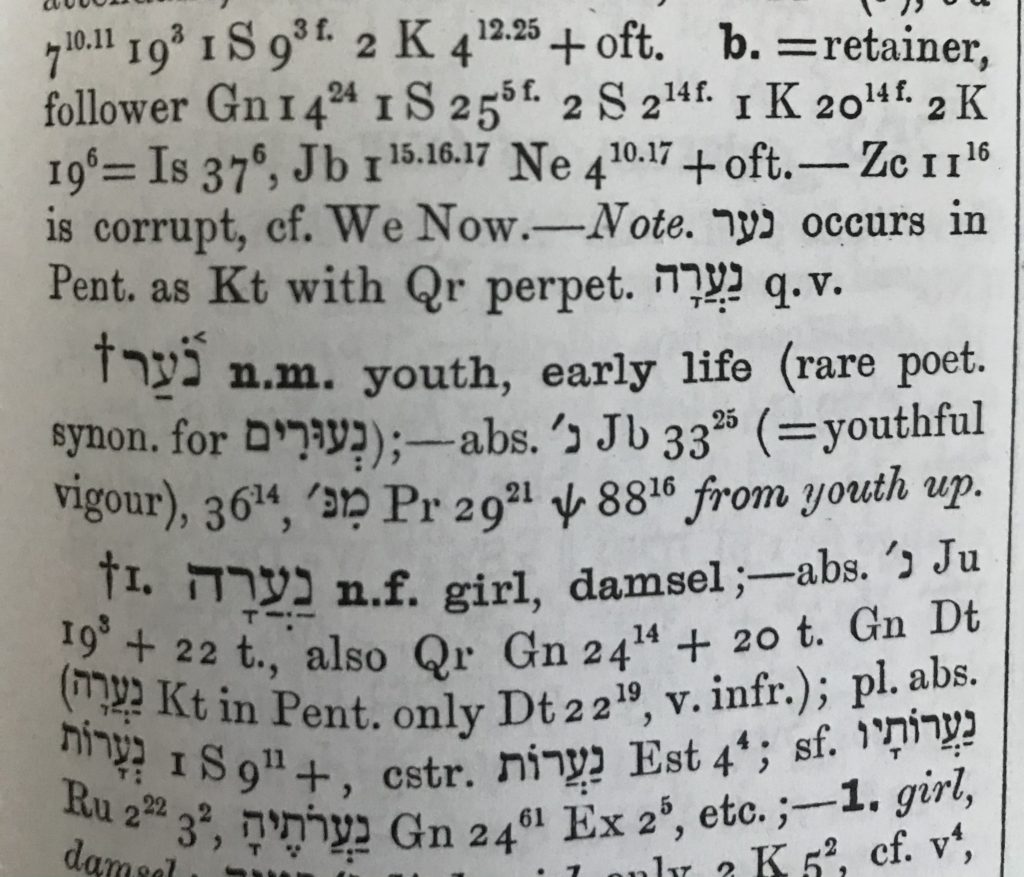

This second project has the name ‘Misogynoir to Mishpat’. ‘Misogynoir’ refers to misogyny directed towards Black women, and ‘Mishpat’ is a Hebrew word used in the Bible, which means ‘justice.’ The project is necessary, because the ability and capacity of people of African descent to produce knowledge – such as conducting research, writing and publishing – is often overlooked, pushed to the peripheries, obstructed, or denied. This is especially true for women of African descent. ‘Misogynoir to Mishpat,’ ‘M2M’ for short, will serve as a corrective by resisting and filling this gap in knowledge production. The very title says a lot about who we are and what we strive to do: we strive to move away from the hatred and discrimination of Black women toward fulfilment and social justice.

The challenges for women of African descent are stark, unsettling and undeniable. In my home country, the U.S., for instance, it has recently been revealed that even when all things are comparable (education, training, number of years in work, etc.), African-descended women earn staggeringly less by retirement than their white female counterparts.[i] While there has been a great deal of discourse about the gendered pay gap – and there should be! – African-descended women are doubly discriminated against, and consistently left behind.

Not only are their work contributions valued less and paid less, but there is also other workplace discrimination: such as bullying and other exclusionary practices, including being refused opportunities for promotion, often a consequence of racial biases. African-descended women in the U.S. (to give an example from the setting I’m most familiar with) are significantly economically disadvantaged, as they are also the group who bears the heaviest student loan debt. This means that African-descended women are often precluded from wealth acquisition strategies, such as home purchases, and are also less able to help defray the cost of higher education for their own children, such as via home equity loans. In short, this creates a downward racial-gender spiral.

As an African-descended woman academic, it is concerning to me how invisible we are. A 2017 article, ‘Black Women Professors in the UK,’ shows that white women and women from certain other ethnic minorities are gaining some measure of presence and visibility in universities. But we represent less than 1% of the British academy. Figures in the U.S. are only slightly better.[ii]

While it is good to see diversity increase, with better representation by South Asian women, for example, as an African-descended woman academic, it is concerning to me that our invisibility persists. When we African-descended women are made invisible, so is our research and our writing. In the course of this, the public declarations of universities wanting greater inclusion, are overshadowed by the private resignation to a status quo which continues to deny our relevance and importance.

‘Misogynoir to Mishpat’ deliberately alludes to ‘Mishpat’, a biblical word, because much of the resistance to inequality is grounded in religious institutions, particularly within the Christian faith. Mishpat, ‘justice,’ is a term which occurs in the Bible over 400 times. It is the primary standard by which the Bible writers understood God to evaluate their faithfulness and righteousness as people of God.

Misogynoir is a portmanteau word which combines ‘misogyny,’ or ‘hatred of women,’ with ‘noir,’ which is ‘Black’ in French. The word is apt for me, because it refers openly to the recognition that women of African descent are prejudiced against and nearly non-existent when it comes to representation in the academic study of religions. In the UK, because the term ‘Black’ has often been expanded to include non-African-descended women (that is, ‘anyone “of color”’), the situation of erasure becomes even more acute and problematic.

Through M2M, we are working to cultivate a strong relationship with churches and community activists who share our concerns. There are many issues to address, from lack of representation in politics and higher education, to poverty and over-incarceration, to lack of mental health and other medical resources, and environmental racism – all of which plague African-descended women disproportionately. To give one example, in the U.S. approximately 70,000 Black women and girls are ‘missing.’[iii]This is a staggering statistic. It might point to other crimes: some may have run away from abusive relationships, others may have been kidnapped, murdered, or sex trafficked. But these women and girls matter. They belong to families and communities who feel their absence and need their loss to be acknowledged and addressed to make them feel whole again. M2M has worked to form partnerships with women in various countries including: Kenya, the Netherlands, Ghana, the UK, the US, France, and South Africa. We want to work with African-descended women in religious academia and religious leadership across the globe: women in the World Council of Churches, women who are local pastors, and lecturers and professors in biblical studies, theology and ethics. We are seeking to strengthen the contributions of them all.

2) What are your aims, vision and hopes for M2M?

Postgraduate students of color often wish to engage in research which amplifies their own backgrounds and cultures. But these students will disproportionately fail to complete their degrees, or go on to fail their viva. And sometimes – I would venture to say, often – this is because universities do not have qualified academics who can engage with, supervise or examine such research. An examiner may decide that a student is inadequate, because they, as examiner, lack knowledge of what the student has outlined in their research. This means that not only are academics of color under-represented but postgraduates of color also stay under-represented.

Our research network seeks to draw attention to such gaps, so that we can walk alongside and support postgraduate students, in particular African-descended women postgraduates. We can assist in creating mentorship and visibility for them – even when they do not have scholars of color in their institutions. We also want to ensure that the research agendas of African-descended students are supported, that they are hired in full-time tenured posts, and that their work is valued in the university system.

We are proactively engaged in the current funding cycle, with the intention of being able to provide such support. Currently, African-descended women (few as they are) are much more represented as independent scholars than as scholars in stable, permanent posts. This marginalization is exacerbated by institutions not considering them for, or not involving them in, significant grants, or in training on how to make an application for a grant. Moreover, such grants are often not even open to, or actively publicized among, independent scholars. Currently, programs like Marie Currie, for instance, which are highly competitive, in my view effectively bypass people of color without any accountability. This must stop.

Our new M2M website will amplify the voices of women of African descent who are religious leaders or scholars or students of religion and theology by: highlighting their achievements (promotions, PhD awards, new pastoral posts), sharing career and information resources (including publications, but also collegial opportunities, such as funding or grant writing possibilities) and disseminating teaching resources, such as ‘video shorts,’ of 3-5 minutes in length. Taken together, these will explain more about, promote, and celebrate African-descended women’s contributions to academia and religious communities. This will include the ongoing work of the Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians (‘the ‘Circle’) and by womanist scholars.

We will post monthly profiles of women. Please see our profiles for Mitzi Smith and Esther Mombo! We also have a new M2M blog series: ‘Conversations in Race, Gender and Religion’ (the call for contributions is here) where we examine our intersectionality more closely. We ask, for instance, ‘In what ways can women in Kenya find synergy with women in Sheffield, England? How might their goals differ? How are their goals compatible?’ And this is just one example of what we hope to grow and nurture into a richly diverse resource.

By balancing these needs of religious leadership and academic religious thinkers with community objectives, I hope we will make a significant difference in the lives of African-descended women and girls.

3) The Shiloh Project is focused on intersections between ‘rape culture’, ‘religion’ and ‘the Bible’. There are some synergies with M2M, particularly given the shocking vulnerabilities of Africana (that is, African-descended) women to gender-based and other forms of violence, including in biblical texts and in religious or religiously influenced communities, right up to the present. How can we support each other’s projects and endeavours?

It’s true that we have a bit of intersection. There are many social issues that womanist scholars, for example, seek to address – and women who emerge from vulnerable communities frequently emphasize wanting to increase the agency of members of their communities.

Historically, Black American women, as one example, have struggled against ‘Christian’ assumptions of the sexual availability of the Black female body. In other words, women and girls who are African-descended, were regularly raped with impunity. Yet, the rhetoric created was that slave holders were ‘bewitched’ by these vulnerable people. White men could rape Black women and girls without being criminalized for it. Instead, the victims were blamed. Christian theology was not guiltless in this.

During the Antebellum, pregnant Black women thought to ‘require’ severe beatings, could be and were beaten, and sometimes beaten to death. A hole was dug into the ground and the woman was placed over the hole with her belly inserted into the ground. This was done to ‘protect’ the soul of the unborn child while the woman’s flesh was beaten from her body, her blood soaking the ground around her.

In Christian teachings, there is sometimes this ‘Platonic’ assumption that ‘the spirit’ and ‘the flesh’ are antithetical to and separate from each another. So, according to this, the body can be destroyed and the spirit spared. But the assumption that a person’s spirit is not aggrieved at the evil of destroying that same person’s flesh, as if we can physically torture the body without causing trauma to the person’s very spirit…

I must visit Toni Morrison’s Beloved to tease this out a bit further. Baby Suggs, a character in the novel, walks with other African-descended people into a clearing in the woods. This is significant, because the woods were frequently regarded as ‘wilderness,’ or as a ‘wild and dangerous’ sphere of uncivilized society.

Baby Suggs preaches a sermon in that forest which tells the members present to revalue their flesh. She encourages them to take every inch of who they are, and to find something there to love – and to love it fiercely. Black beauty was all but an oxymoron to most in 19th century America. To be beautiful, lovable, intelligent, human was to be white. But Baby Suggs encourages people to create a new theology of self love which renounces the hatred espoused by the dominant majority culture.

With that in mind, women who have been abused need to touch those harmed and swollen joints, the discolored limbs, and love themselves. Those who have had body parts torn and bloodied through rape and other forms of assault, must practise looking at themselves, touching and loving themselves. Just as Baby Suggs encourages her congregants to touch the spaces between the grooves of fleshly abuse, so also we, in M2M and Shiloh, need to encourage people to touch and reclaim all those spaces which were stolen. And, like Baby Suggs did, we need to encourage people to love their bodies, hearts and minds.

In fact, M2M can be summed up in this way: Black women from every land and every religion, are summoned to come and kneel at the altar of self acceptance. We want to encourage all of them to love themselves fiercely – body, mind and spirit. And, for those who are academics, we urge them to share that love of mind and spirit in their research and writing. We will walk alongside you. We only ask that when your legs get strong, you do not run away, but you turn to your left or your right, and you walk alongside someone else. As you stand with us, we also will stand with and support the amazing work of the Shiloh Project.

Indeed, we may kneel as hundreds, but we will stand as tens of thousands.

Thank you, Dr Nash. Thank you for telling us about your important work. We look forward to watching M2M grow and thrive.

_____________________________________________________________________

Dr CL Nash recommends the following sites for further reading:

‘Black Then,’ a website to address American Black History, here

‘Black Women’s Experiences in Slavery’ (chapter 2), here

‘Word to the Wise: African American/Black Women and Their Fight for Reproductive Justice,’ here

[i] See the Pew Research Center, which reports the staggering pay differences that can add up to in excess of $1M by the time of retirement. You can see more here and also look at this reference about Black women’s lack of fair pay. For another perspective, see also here. For more statistics on the sharp disparities along color lines, see also this.

[ii] Dr. Nicola Rollock indicates that there are only twenty-five Black female professors (see here). According to her research, this is due to such issues as Black women being bullied, feeling forced to work harder and, ultimately, being drained when working as academics. The Guardian supports her findings. See ‘Black women must deal with bullying to win’, here.

[iii] For more information on the missing Black women and girls in the U.S., please see this reference by the Women’s Media Center. Also, please see the Black and Missing Foundation (here), which also explores the issue of Black Americans missing – an under-reported phenomenon. Because a portion of those missing are presumed to be sex-trafficked, there are activist groups, which are also monitoring and aiding with that situation. Check out Black Women’s Blueprint as one example (here).