Here’s hoping 2021 brings positive action and results after what has been a difficult and challenging 2020, not least for groups already very vulnerable to and suffering from gender-based violence.

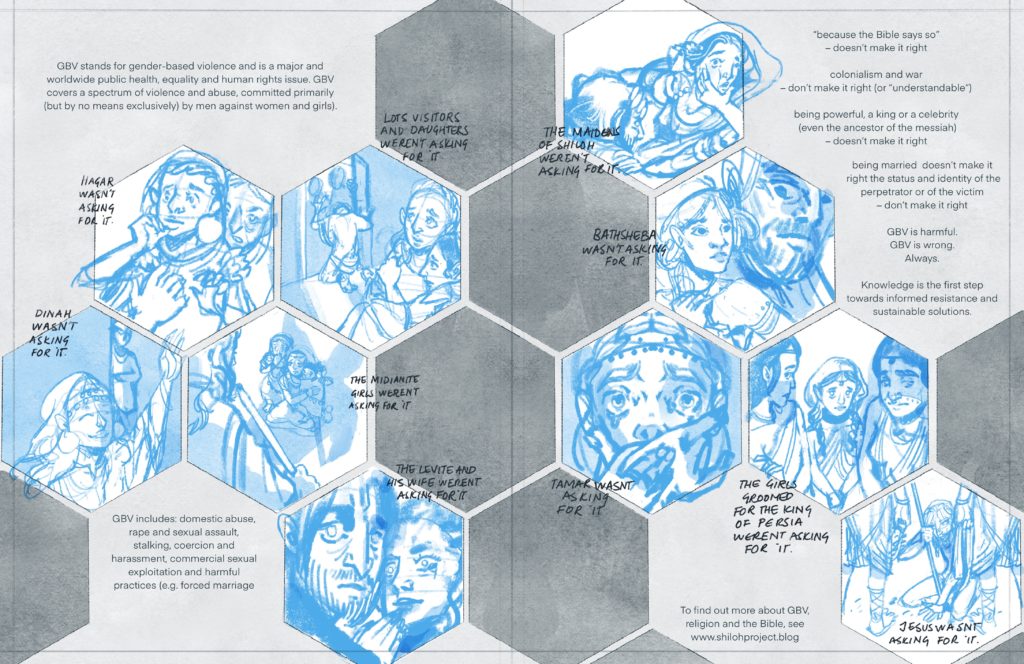

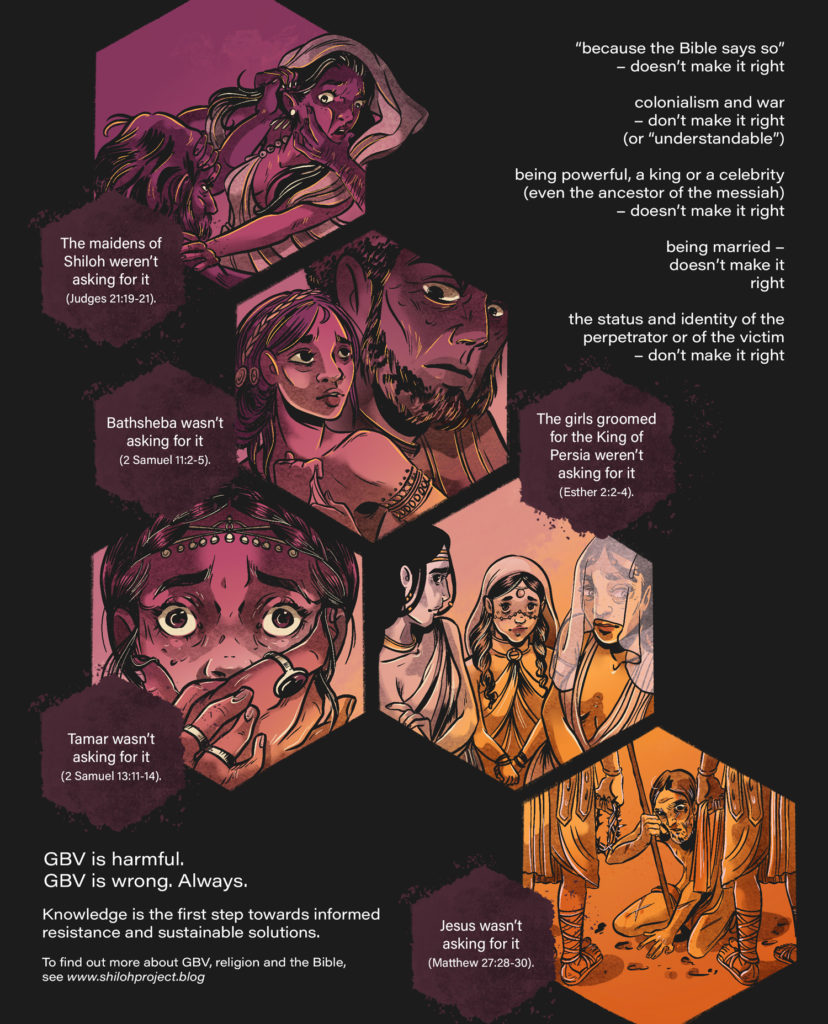

Here’s a resource we hope many of you will find useful. This artwork is by Pia Alize, a graphic artist who has produced stunning images responding to gender-based violence and MeToo in India. You can see some of her other magnificent art, or contact Pia at: www.pigstudio.in

We hope these images, capturing references to gender-based and sexual violence in the Bible, will open up conversations that lead to social justice action in faith-based communities and beyond. We will be using them in workshops and teaching sessions. Our hope is they will appeal to a wide and inclusive audience.

If you require jpg files, please contact Johanna: j.stiebert@leeds.ac.uk

Funding for the production of these images was provided by the generous support of a grant from the AHRC UKRI, ‘Resisting Gender-Based Violence and Injustice Through Activism with Bible Texts and Images’.